Pacific aquaculture transition - What we heard report phases 1 and 2

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- What we heard

- Conclusions and next steps

- Annex A: What we heard by engagement group

- Annex B: Summary of survey findings

- Annex C: Proposed metrics to measure success

Executive summary

On July 29, 2022, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard and her Department released a discussion framework to guide engagement on the development of an open-net pen transition plan. The discussion framework proposed four main objectives for the transition plan. During the engagement process, Canadians have shared a variety of views about these proposals. The purpose of this What We Heard report is to provide parties with an opportunity to learn about and respond to feedback the Department has received during phases 1 and 2 of engagement. In particular, given the diversity of ideas and perspectives which First Nations and stakeholders have expressed during consultations, it is important that the Department understand what specific concerns and other considerations should be taken into account when considering the wide variety of perspectives and options which relate to the possible outcomes and timelines of a transition plan. Below is a summary of what we heard for each objective:

Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture: Some participants advocated for the immediate removal of marine salmon aquaculture, while some supported a performance and outcomes-based transition focused on the goal of minimizing or eliminating interactions between wild and cultured fish. Some expressed preference for a rapid transition while others felt the timing should align with the availability of alternate production methods. Some feedback was focused on specific technologies, while other input targeted results. Participants sought clarity from the Department on both the specific objectives of the transition, and on the timelines associated with meeting the objectives.

Trust and transparency: Participants in engagement sessions highlighted the key importance of improving trust and transparency. Many participants expressed frustration that the Government of Canada was not playing more of a lead role in effectively communicating its overall conclusions related to the science of aquaculture, while many other First Nations and stakeholders articulated a distrust of DFO science and concerns related to potential conflicts of interest. Specific suggestions included: the establishment of an independent science review process; an increase in third-party monitoring and reporting; greater transparency in decision-making, and the enhancement of communication related to science and management objectives and performance.

Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships: Participants noted the complexity and importance of potential impacts to Aboriginal rights and title and self-determination. A number of First Nations with aquaculture in their territories expressed strong support for the open-net pen aquaculture sector, and urged the Government of Canada to respect their Indigenous right to determine whether or not the conduct of aquaculture should take place in their territory, and upon what terms. These Nations argued that the impacts of closing this industry would be catastrophic on their communities, and urged the Government of Canada to conduct further economic assessments and to engage in meaningful consultations to develop plans more specific to, and respectful of, individual communities. Most First Nations either directly or indirectly indicated their opposition to marine-based open-net pens and advocated for immediate removal of open-net pens as an action required to address their concerns that open-net pen aquaculture poses a threat to wild salmon. All participants expressed support for enhanced First Nations' engagement and participation in the management of aquaculture, including through collaborative planning and decision-making. Participants also expressed broad support for the incorporation of Indigenous-led science into aquaculture management and the science review process.

Growth in B.C. sustainable aquaculture innovation: Participants generally voiced support for innovation in aquaculture in B.C., and generally supported the vision of B.C. being a world leader in the development and adoption of next generation sustainable aquaculture technology. Participants showed broad support for the adoption of technologies that would minimize or eliminate environmental impact, but there were differing views on the types, timelines, and feasibility of different innovations. Many participants supported the establishment of a Centre of Expertise for aquaculture innovation, with a potential area of focus being First Nation-led science and management. Some participants expressed a desire for a whole-of-government approach to attract investment and advance innovation and development of new alternative aquaculture production systems. Other participants did not support the use of technology that is not proven to completely separate all cultured fish, including water and waste, from wild fish and fish habitat. Views on transitions to other types of aquaculture (e.g., marine plant, land-based, and shellfish) were generally supported, but not generally seen as a realistic replacement for the open-net pen aquaculture industry in coastal communities.

Introduction

Engagement on a new framework for sustainable aquaculture in British Columbia

The Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard has a mandate from the Prime Minister of Canada to continue to work with the Province of British Columbia (B.C.) and Indigenous communities on a responsible plan to transition from open-net pen salmon farming in coastal B.C. waters by 2025. On July 29, 2022, the Minister and her Department released a discussion framework to guide engagement on the development of an open-net pen transition plan (the transition plan, the plan).

The purpose of this What We Heard report is to provide parties with an opportunity to learn about and respond to feedback the Department has received during phases 1 and 2 of engagement. In particular, given the diversity of ideas and perspectives presented in this report, the Department wants to learn what specific concerns and other considerations should be taken into account when considering these different proposals. Extensive engagement has taken place with First Nations, marine finfish industry, ancillary and land-based aquaculture industries, local governments, environmental groups, researchers and academics, the general public, and other parties on the development of a transition plan.

Additional engagement with First Nations and key stakeholders is planned following the release of this What We Heard summary report.

Summary of engagement in phases 1 and 2

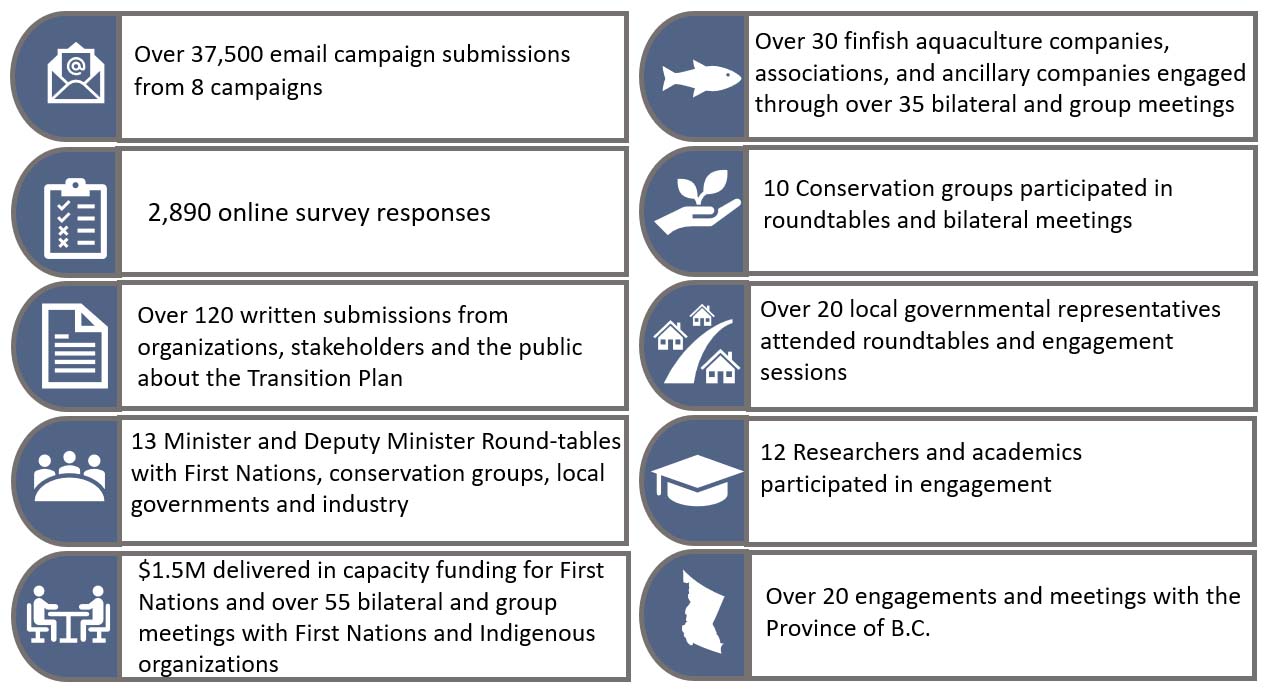

Long text version

Summary of engagement in phases 1 and 2

- Over 37,500 email campaign submissions from 8 campaigns

- 2,890 online survey results

- Over 120 written submissions from organizations, stakeholders and the public about the transition plan

- 13 Minister and Deputy Minister roundtables with First Nations, conservation groups, local governments and industry

- $1.5M delivered in capacity funding for First Nations and over 55 bilateral and group meetings with First nations and Indigenous organizations

- Over 30 finfish aquaculture companies, associations and ancillary companies engaged through over 35 bilateral and group meetings

- 10 conservation groups participated in roundtables and bilateral meetings

- Over 20 local governmental representatives attended roundtables and engagement sessions

- 12 researchers and academics participated in engagement

- Over 20 engagements and meetings with the Province of B.C.

What we heard

The following section provides an overview of feedback related to the four objectives outlined in the discussion framework:

- Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture

- Trust and transparency

- Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships

- Growth in B.C. sustainable aquaculture innovation

This high-level overview provides a summary of ideas and perspectives raised during engagement including through meetings, written submissions, and an online survey. In the interest of brevity, this report does not include all detailed views and feedback shared. This does not imply that there is consensus among participants. All views and feedback received will be considered in the development of a final transition plan. Additional detail is provided in Annex A: What we heard by engagement group; Annex B: Summary of survey findings; and Annex C: Proposed metrics to measure success.

Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture

For the existing marine-based salmon aquaculture industry, the discussion framework aims to create a regulatory climate which will incent adoption of alternative production technology and tools with the goal of progressively minimizing or eliminating interactions between cultured and wild salmon. We heard perspectives on:

- Protection of wild Pacific salmon

- Minimizing or eliminating interactions between cultured and wild salmon

- Mitigating impacts

Protection of wild Pacific salmon

Wild Pacific salmon have significant cultural, social, and ecological importance to First Nations and British Columbians, however, they are in serious, long-term decline and there is urgency to take bold action. All participants agreed on the importance of protecting wild salmon but there were differing views on the level of risk posed by open-net pen salmon aquaculture, and the resulting likelihood of potential impacts of salmon aquaculture on wild salmon populations. Some participants felt strongly that on balance, science clearly indicates that aquaculture has had significant negative impacts on wild salmon populations, while others expressed that when analysed as a whole, the body of science available today does not support the concern that that salmon aquaculture is having a quantifiable impact on wild salmon populations. Participants agreed on the importance of risk-based decision-making, however, some indicated that any risk to wild salmon is unacceptable while others supported risk-analysis at the population level. Widely differing views related to risk tolerance among participants led to a wide range of perspectives on the recommended outcomes and timelines required for a successful transition plan.

Many First Nations stated that open-net pen aquaculture in B.C. has had population-level impacts on wild salmon. These First Nations asserted that the current regulatory approach impacts their constitutional rights related to food, social, and ceremonial fishing as well as in some cases commercial fishing for salmon. They asserted their right to provide input to decisions on aquaculture because wild salmon, upon which they rely, migrate past open-net pens. In most cases these First Nations also articulated a distrust in DFO Science and shared the perspective that risk assessments have not accurately reflected the negative impacts of open-net pen salmon aquaculture. While these First Nations support an objective to reduce risk associated with aquaculture, in most cases they were of the view that the only solution is an outcome based on a requirement for all open-net pens to be out of the water within a short time frame.

Minimize or eliminate interaction between cultured and wild salmon

Participants who felt strongly that science indicates that open-net pen aquaculture poses risks to wild salmon were more likely to support a near-term (e.g., by 2025, or as soon as possible) removal date for all open-net pen aquaculture operations. Others viewed a transition that did not allow reasonable time for industry to adapt and innovate to meet new requirements as an unjustified, arbitrary, and highly disruptive approach, inconsistent with DFO scientific risk assessments.

Some participants suggested that the Department remove all open-net pens from the water and focus the transition on the adoption of new technology and production methods as they become commercially available and on worker/community economic supports. They suggested the focus would be on supporting the development and adoption of new available production methods or community and worker transitions as quickly as possible and requiring industry to evolve in order to continue to operate in B.C.

Another model suggested by participants was a sequenced, structured approach focused on the urgent removal of open-net pens from known wild salmon migration routes and the future potential removal of sites in sequence based on priority from a migratory route perspective. Participants suggested that this could be modeled on the Broughton Aquaculture Transition Initiative, incorporating lessons learned. In some cases this was proposed as a structured removal; others proposed multiple decision points with the ability of First Nations to decide whether or not aquaculture would continue in their core territory.

Some participants supported the adoption of incremental performance targets and the development of key performance milestones (e.g., pest and pathogen transmission) that would become increasingly more stringent and would be tracked. They stated that this would allow a transparent approach to assess the progress in progressively minimizing or eliminating interactions, and could provide time for industry to adopt new technology in response to increasing performance standards.

As for an outcome based approach, participants highlighted that a very restrictive outcome (no open-net pens) in a short timeline (5-10 years) would not allow the existing industry any opportunity to adapt, and would result in significant dislocation as the current marine finfish industry would phase out operations in B.C. They noted that in a scenario where there was either a more flexible outcome (metrics which continued to push performance standards) and a longer timeframe (10 years or more), significant investment by industry would be essential to push innovation and the evolution of technology.

Participants noted that in addition to Atlantic salmon aquaculture, there are other forms of finfish aquaculture in British Columbia, including Chinook salmon and sablefish. They recommended that the transition plan take into account the unique aspects of cultivating these different species and be clear what implications, if any, the plan would have for culture of these species.

Many First Nations asked the Government of Canada to defer decision-making to First Nations for activities within their core territory. In this scenario, it was noted that First Nations would decide whether or not they wanted to pursue partnerships with industry, and that First Nations would work together and with industry, federal and provincial governments, and others in identifying plans to balance a support for industry with environmental and wild salmon monitoring and protections.

Mitigating impacts

Participants noted that moving to progressively minimize or eliminate interactions between wild and cultured salmon would create significant disruption to the aquaculture industry, First Nations with aquaculture in their territories, and coastal communities in B.C. They noted that specific impacts, however, would largely depend on the stated outcomes and the timeline adopted in the transition plan.

A number of participants spoke to the commercial viability of various innovative alternative production methods, expressing differing opinions about how long it would take for these technologies to become commercially available or to be deployed. Some note that technology to support a full transition to land or marine-based closed containment aquaculture is currently in a research and development phase, while others pointed to innovation happening quickly. Participants noted that within B.C., one of the challenges to innovation is that adoption of new technologies will be highly reliant on the stability of current supply-chains and ancillary services. It was expressed that these services are under severe stress from current reductions in production within the province and should they close as a result of impacts on the open-net pen industry, they would be difficult to reestablish within B.C. As well, a number of participants voiced concern that it is unlikely that a future land-based or marine closed containment aquaculture industry would replace the scale of economic benefits and jobs provided by open-net pen salmon aquaculture, and such an industry would likely be focused on specific geographic areas with the characteristics required for its success (e.g., available power, water, etc.).

With respect to an outcomes based approach, a number of stakeholders provided feedback that a very restrictive outcome (no open-net pens) in a short timeline (5-10 years) would not allow the existing industry an opportunity to adapt and would result in significant dislocation as the current marine finfish industry would phase out operations in B.C. Stakeholders noted that in a scenario where there was either a more flexible outcome (metrics focused on increasingly stringent performance standards) and a longer timeframe (10 years or more), significant investment by industry would be essential to push innovation and the evolution of technology.

Many First Nations on the B.C. coast have also provided feedback to the Department stating that they are actively engaged in partnerships with the aquaculture industry and in many cases have local economies highly integrated with the marine finfish aquaculture activities. This includes many Indigenous-owned businesses which are heavily or exclusively reliant on the aquaculture industry. They stated that today’s agreements between First Nations and industry are comprehensive and tied to community self-determination and economic self-reliance. Many First Nations told the Department in consultations that a transition plan which aims to progressively minimize or eliminate interactions in a manner that creates significant disruption to industry would also have a negative impact on Aboriginal rights and title, which would have devastating social impacts to affected communities.

Many First Nations and other participants expressed that a rapid transition could result in hundreds of millions of dollars in loss of economic opportunities and jobs, which could lead to local economic crises as well as employment and health consequences in rural and remote coastal communities. These First Nations urged the Department to undertake a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of various decisions at the First Nation level, and meaningful consultation with respect to these impacts prior to a decision being made. It was highlighted by participants that mitigation of these impacts could require considerable economic supports for First Nations, communities, and workers to ensure a transition to other economic opportunities and that a solution should not be “one size fits all”.

Participants and local governments expressed concern that smaller coastal communities and Indigenous communities with economies heavily integrated into the aquaculture sector would face significant negative impacts should the plan advocate for a fast transition from current technologies. Some of these participants noted that a shorter transition could necessitate community supports, whereas a longer-term transition would allow communities and industry to transition to alternative production technologies, alternative species, or other economic opportunities. Some coastal communities most directly affected by the transition plan also urged a less rushed process of consultation and engagement with impacted communities and First Nations and noted that with the potential for long term very large impacts on local workers and economies, there could be a significant requirement for economic supports for these communities.

Many participants in phases 1 and 2 of the engagement process noted that potential impacts associated with various possible outcomes and timeframes of a transition plan are broad and deep, and require a response centered on a whole-of-government approach. In general, all participants urged the Government of Canada to look at these issues in a holistic manner, to make clear and rational decisions based on sound science, and to consider the broad implications related to the direction taken in the transition plan. Some participants noted that a long-term vision and strategy would create certainty and promote stability (from an economic, regulatory, and good governance perspective), and that setting clear regulatory expectations would provide industry, First Nations, and investors with guidance on elements such as location of business development, technologies to be used, etc. They stated that a whole-of government approach for attracting investments into the future would provide industry with certainty of operations. Some participants noted a Centre of Expertise for aquaculture innovation could foster collaboration and innovation which could further attract investment. Feedback included the view that use of developmental/longer licences is a key factor in establishing a stable regulatory environment if the plan is seeking to have industry invest in new technologies.

Trust and transparency

The discussion framework identified a need to improve trust and transparency in processes which assess and respond to new scientific information and demonstrate clear and quantifiable improvement in sustainable performance, to ensure Canadians have confidence in the management of aquaculture. We heard perspectives on:

- Monitoring and reporting

- Indigenous guardian programs

- Independent science review

- Improved communication

Monitoring and reporting

Many of those who participated in engagement supported an increase in monitoring and enhanced oversight of the aquaculture industry to further validate industry reporting. Some participants noted that there is not easy to find and understandable information available to the public on existing monitoring, auditing, and enforcement. Some participants expressed that data collected through monitoring should be made public in a standardized and understandable way, and datasets should be available in usable formats in a timely manner if requested for scientific analysis. In addition to enhanced government monitoring and oversight, some participants advocated for the use of ‘independent’ monitors, to verify government’s monitoring of industry. Some organizations, particularly conservation organizations, stated that their lack of trust in DFO caused them to question the intentions of integrity of the Department’s reporting. Industry representatives questioned why the Department is not more assertive in the public domain to defend their monitoring, audit and enforcement practices, which they believe are some of the most stringent in the world and should be communicated more proactively in the public domain.

Indigenous guardian programs

Many participants stated that Indigenous guardian programs, where First Nations provide regulatory oversight and monitoring of aquaculture activities, are helpful in increasing trust and transparency. It was noted that this was not necessarily a “one size fits all” solution and formal guardian programs were not the only way to achieve hands on Indigenous engagement or to build trust. Almost all participants in the engagement sessions supported enhanced Indigenous monitoring, although some participants stressed the additional need for ‘independent’ monitors/ guardians.

Independent science review

The Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) coordinates the scientific peer review and science advice for Fisheries and Oceans Canada and publishes departmental scientific advice and information on issues, including aquaculture. Concern was expressed by some participants about a lack of the integrity of the CSAS process, while others expressed concern that the Department is making decisions inconsistent with its own science advice.

Some participants acknowledged the importance of CSAS, or the concept of an independent peer review process, while others expressed concerns that CSAS processes are subject to conflicts of interest, participant bias, and a lack of adherence to proper risk assessment or application of the precautionary principle. Concerns were raised that departmental science is not inclusive of wider scientific community research, cumulative effects assessment, or Indigenous science and knowledge. Some participants pointed to the recent testimony at the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, in which a number of concerns were raised related to aquaculture science processes.

Recommendations for improving the current science review process ranged from the option of working through the existing CSAS processes to ensure outstanding concerns were addressed, to a call to establish of an independent aquaculture science advice board for the Department. Some participants provided examples of external science review processes successfully used in other scenarios, and suggestions included options which ranged from the engagement of more academics, to the identification of possible bias (where these experts receive funding from - with the option to exclude those who receive funding from a source which may be considered biased), to science reviews by the Province of B.C., or the selection of ‘independent’ scientists to form a review panel. Participants also proposed that Indigenous-led science be more explicitly included in science processes. In some cases it was recommended that oversight could be provided through appointment of an external or arms-length aquaculture Science Advisor for Pacific Region.

Improved communication

Some participants expressed the view that the Department does not effectively share data nor effectively communicate the scientific research it conducts. Some participants felt that the language used in the discussion framework and other documents was vague or unclear, and made it difficult for First Nations, the public and stakeholders to understand information on aquaculture transition.

Some participants indicated that availability of raw datasets in a more usable format (i.e., downloadable to analysis software) would be helpful to those outside the Department. In some cases they expressed that they did not find the format of the open data currently published by the Department useful. Additionally, there was an expectation expressed that the Department should make publicly available all of the raw data used in research or CSAS processes so that external scientists can validate the work of the Department.

To improve communication, participants suggested that science information be provided in plain language that is accessible to all Canadians and that a departmental communications plan be established to focus on communicating aquaculture science information to the public. Some participants felt that the Government’s communications on aquaculture management needed to provide better and more relevant information to help the public understand how well the industry was performing, and what type of impacts the sector was having on the marine environment and on wild salmon populations.

Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships

The discussion framework supports enhanced First Nations’ engagement in the management of aquaculture through collaborative planning and decision-making. We heard perspectives on:

- Engagement process and impact on the transition plan

- Involvement of First Nations in aquaculture activities

- Indigenous knowledge in aquaculture management

Engagement process and impact on the transition plan

Many First Nations participants expressed concern that the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was not well reflected in the discussion framework, and they stated that it should be better incorporated into the transition plan. Participants discussed the impacts of the transition plan on Aboriginal rights and title. First Nations who are engaged in the salmon aquaculture sector and First Nations who may or may not have salmon aquaculture in their territories but are concerned about possible risks to wild salmon posed by aquaculture both agreed that First Nations need to have more engagement in the future decisions related to open-net pen aquaculture. Participants expressed concern that timelines for engagement are too short and not aligned with the spirit of reconciliation and do not allow the parties to conduct meaningful consultation.

Some participants expressed that explicit recognition of modern treaties and associated governance structures should be included in the transition plan process. Participants from Modern Treaty First Nations expressed concerns that the Department has not distinguished Modern Treaty Nations from non-treaty Nations in its consultation process or in the discussion framework.

From all perspectives, there was an expectation that the obligation of the duty to consult is high for the Government of Canada on issues related to open-net pen aquaculture. Views on the breadth of the consultations ranged from feedback that consultation should focus on those First Nations within whose core territories aquaculture takes place, to feedback from some Interior Nations who stated that they should be engaged in any decision where there was a likelihood that a salmon which would have to migrate past an open-net pen farm would at some point in its life migrate by their inland community.

Many coastal communities with economies highly reliant on the aquaculture industry spoke about the severe impacts which their communities would face should government remove open-net pen aquaculture from their territories. All First Nations urged government to continue to engage in a deep and meaningful way with First Nations on these important and complex issues. Overall feedback was clear that engagement needed to happen at the Nation level, and that a customized approach which engaged specific communities in a dialogue about their own territories was necessary, resulting in a ‘transition plan’ for each First Nation.

Involvement of First Nations in aquaculture activities

Most First Nations with territory in proximity to aquaculture operations expressed their desire to monitor and oversee aquaculture activities in their territories, and to build and restore capacity to undertake activities for the long-term recovery of wild salmon and other components of healthy and productive ecosystems and communities. Many First Nations spoke of the benefits associated with partnership agreements with Industry, and expressed their views that their rights include the ability to make informed decisions related to the management of the aquaculture industry in their territories.

Many First Nations and coastal communities felt that the establishment of area-based aquaculture management would be a positive step toward supporting involvement of First Nations in aquaculture activities. Some participants expressed that collaborative governance zones, similar to governance mechanisms already implemented in the Broughton Aquaculture Transition Initiative, would provide First Nations with mechanisms to make decisions ranging from a phasing out of open-net pens, to new locally developed enhanced management regimes based on specific ecological, social, and cultural objectives.

Indigenous knowledge in aquaculture management

Participants expressed the desire to see Indigenous-led science and traditional practices from Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers incorporated in management and decision-making. Similarly, there was a desire to see increased Indigenous-led monitoring and reporting through Indigenous guardian programs. In some cases First Nations shared information related to their vision to move forward in a more integrated management role with respect to oceans, fisheries and aquaculture management in their territories. Many Nations have already done significant work to develop their vision for their territories. In many cases this includes First Nations playing a fundamental role as managers within their own territories, with the science and research expertise to formulate and carry out their own independent monitoring, laboratory testing, research, science, and enforcement.

Growth in sustainable aquaculture innovation

The discussion framework described this as a whole-of-government approach to attract investment and advance innovation and development of new alternative production technology systems, including closed containment, to make B.C. a global leader in innovative aquaculture, which minimizes environmental impact. We heard perspectives on:

- Desire to innovate

- Conditions to foster innovation

Desire to innovate

Participants communicated their interest in moving towards the use of new alternative technologies and/or species. Industry indicated interest in fostering continuous improvement and supporting Canada in becoming a world leader in the deployment of sustainable aquaculture technologies. Some First Nations and other communities indicated potential interest in ideas such as Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture, where nutrients fed to finfish generate high-quality waste that shellfish and marine plants depend on to grow. Some participants noted that moving towards this type of innovation would help support economic diversification of the aquaculture sector and coastal communities.

Participants from conservation organizations expressed the view that new in-water technologies were not acceptable and would not meet the objectives of an open-net pen transition if they did not eliminate all interactions, including any non-treated exchange of water, between farmed fish and the outside environment. Interests from these groups focused on transitioning communities away from aquaculture to other industries, like tourism.

While industry expressed interest in continuing to innovate and adopt new sustainable technology approaches, they expressed concerns related to possible timeframes or outcomes of the plan which would not allow flexibility required for them to innovate.

Conditions to foster innovation

Participants noted that sustainable aquaculture innovation is a broad term and incenting investment requires clarity on what types of technology will be encouraged. Industry provided feedback that investments into infrastructure require security and stability and the opportunity to recoup investments. Participants indicated that clarity is required on whether in-water closed containment or other on-water alternative production methods are included in this vision or only land-based production models, and that the Governments of Canada and B.C. should be clear on what types of technology they want to attract.

In order to transform B.C.’s aquaculture sector, industry stated that they require a certain level of stability and time to allow for the implementation of innovative technologies. It was noted that development and adoption of new and innovative technology involves taking risks, can be very expensive, and requires research and testing within a stable regulatory environment.

Coastal communities noted that workforce requirements and supports need to be identified in the transition plan, and that a skilled and flexible workforce that includes local First Nation workers would help adapt to a highly innovative industry. There are perspective that attracting and retaining workers is difficult when industry is in a climate of uncertainty. It was also noted that the recent closure of farms in the Discovery Islands has had a significant impact on industry and communities, and it was noted that no specific economic supports have been announced to mitigate these challenges.

Community infrastructure was identified by some participants as an important consideration in moving towards the adoption of new technologies. Some participants shared that, in some cases, the physical and geographical location of open-net pens are not conducive to technological advancements due to lack of infrastructure (e.g., access to hydropower, water, etc.). Local governments and First Nations have expressed support for investments in infrastructure that would help support technological advancements in the aquaculture sector. On the other hand, some participants noted that climate change impacts of alternative technologies could be considerable and should be considered in the development of the transition plan.

Conclusions and next steps

A variety of views were shared in phases 1 and 2 of the engagement process. This significant and valuable input will be considered in the development of an open-net pen transition plan.

During engagement, all participants agreed on the importance of protecting wild Pacific salmon but there were differing views on the level of risk posed by open-net pen salmon aquaculture, and the challenge of singling out one possible impact without a more broad context related to possible risks and impacts to wild salmon populations. Some participants advocated for a rapid transition focused on the immediate removal of all marine salmon aquaculture, and others supported a detailed performance and outcomes based transition focused on the goal of minimizing or eliminating interactions between wild and cultured fish. Some participants’ feedback was very focused on specific technologies, while some responses provided recommendations related to performance objectives and targeted results. Some participants expressed that salmon aquaculture is an important and emerging industry in B.C. with significant potential growth, that emerging technologies could help limit interactions with wild Pacific salmon, and that the transition plan presented an opportunity for Canada to be a world leader in the area of sustainable marine finfish aquaculture. The impacts of a transition on the Aboriginal rights and title of First Nations who are involved in salmon aquaculture as well as First Nations who may or may not have salmon aquaculture in their territories but are concerned about risks to wild salmon were key topics of discussion. The complexity and importance of potential impacts to Aboriginal rights and title and self-determination and implications for reconciliation was noted by many participants, as was the importance of improving trust and transparency in aquaculture management.

Overall, participants supported the development of a responsible plan to transition from open-net pen salmon farming in coastal B.C. However, participants had very different interpretations of what the implications were both in terms of timelines and outcomes. Feedback from participants was that a transition can be achieved, but will require clarity on objectives and timelines and regulatory certainty, will need sufficient time to allow for planning and implementation, and will require incentives to support First Nations and communities and to support a transition. Views heard during engagement were, however, highly polarized, and facilitating a solution which meet the expectations of the broad spectrum of those who have a stake in these issues will be challenging.

While reconciliation with Indigenous peoples is a key objective for the Government of Canada, it is worth noting that there is not a consistent understanding or vision of what reconciliation should look like with respect to open-net pen transition. Many First Nations in B.C. are highly engaged in these issues, and have very different interests and expectations related to the transition plan process and the obligations of the Government of Canada.

Upcoming engagement will provide an opportunity for participants to learn about and respond to feedback the Department has received during phases 1 and 2 of engagement. In particular, given the diversity of ideas and perspectives presented in this report, the Department wants to learn what specific concerns and other considerations should be taken into account when considering these different proposals.

Once an open-net pen transition plan is finalized, the Government of Canada will continue to collaborate and engage with the Province of B.C., First Nations, local governments, industry, and other parties on its implementation.

Annex A: What we heard by engagement group

The following section provides an overview of feedback received during engagement sessions with the following groups:

- First Nations and Indigenous groups

- Marine finfish industry

- Ancillary and land-based industry

- Local governments

- Environmental groups

- Researchers and academics

For each engagement group, a high-level summary of ideas and perspectives raised during engagement is presented. This does not attempt to include all views and feedback shared and does not intend to imply consensus on the part of participants. All views and feedback will be considered for the development of a final open-net pen transition plan.

First Nations and Indigenous groups

First Nations and Indigenous groups

Participants from First Nations and Indigenous groups articulated a range of perspectives on the open-net pen salmon aquaculture industry. Some First Nations with aquaculture in their territory want to choose if, when, and how the sector operates in their waters. For some, this means being able to establish partnership agreements with industry and make local decisions on management of the industry in their territories. For others, this means being able to phase out aquaculture in their territories and that they be provided with transition supports. Some First Nations support the self-determination of other First Nations to make decisions about aquaculture in their territories, while other First Nations are calling for the removal of all open-net pen salmon aquaculture in B.C. due to concerns about potential impacts that extend beyond the territory where aquaculture activities are located.

Participants expressed that there would be impacts to Aboriginal rights and title whether open-net pens stay in the water or if they are removed. Some participants expressed interest in better understanding the impacts of open-net pen salmon aquaculture and interest in meeting with other First Nations and stakeholders to share and understand each other’s perspectives. Overall, all participants agreed that protecting wild salmon and respecting Aboriginal rights are top priorities for all First Nations and Indigenous groups.

Among First Nations and Indigenous groups, a number of opinions were shared. The following represent points raised by one or more participants.

Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture

We have heard:

- Interest in Indigenous self-determination and First Nation management of aquaculture and fisheries in their territories

- Salmon aquaculture is a sustainable economic opportunity for First Nations to become self-sufficient and to address issues of food security

- There would be impacts to other local businesses that rely on existing salmon aquaculture infrastructure if the industry was phased out

- First Nations with industry partnership agreements are already holding the industry to high environmental standards and they are developing their own local transition plans

- There is significant interest in area-based aquaculture management, but different views on what that should look like

- Desire to see a transition away from all ocean-based salmon aquaculture based on views that land-based aquaculture is the only alternative technology that would eliminate interactions between wild and cultured salmon

- Land-based aquaculture is not feasible in some territories of First Nations with industry partnership agreements

- Interest in adopting a Broughton Aquaculture Transition Initiative type of process beginning with sites between the B.C. mainland and Vancouver Island (viewed as most linked to migratory salmon routes of interest to Nations that are concerned about the impact of aquaculture)

- The impacts of open-net pens are widespread; they can affect salmon migratory routes and communities down-river

- Should open-net pens be phased out, Government of Canada support would be required to allow communities to transition to other sources of economic development

- Interest in conducting a cost-benefit analysis of the industry that would include the cultural value of wild salmon

- Interest in the Government of Canada conducting a thorough analysis of the social and economic contributions from salmon aquaculture, including year-round employment and other factors

- Language used in the discussion framework such as “progressively minimize or eliminate interactions” suggests status quo

- Language used in the discussion framework such as “progressively minimize or eliminate interactions” puts too many constraints on industry and eliminates the creativity and trials needed to advance innovative solutions

Trust and transparency

We have heard:

- Desire for increased Indigenous monitoring of the aquaculture industry and support for First Nation guardian programs

- Interest in using Indigenous knowledge in combination with innovative technology (e.g., eDNA) to monitor wild salmon and impacts from open-net pens

- Interest in conducting First Nation-led research to better understand all stressors on wild salmon

- Desire to establish an independent science review process that would incorporate Indigenous-led science and include local Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers

- Desire for the Department to release aquaculture data in real-time in order to allow First Nations to perform oversight of activities

- Desire for the Department to use a precautionary approach when there are diverging scientific opinions and when no cumulative impact assessments have been conducted

- Interest in an independent science review process

- Lack of trust in the Department’s science processes and views that the Department is working closely with industry on the development of the transition plan

- Lack of trust that the Department will take its own science into account in the development of the transition plan

Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships

We have heard:

- First Nations want to choose if, when, and how the sector operates in their waters, which includes:

- being able to establish partnership agreements with industry, if that is what they desire, and make local decisions on management of the industry in their territories

- being able to phase out aquaculture in their territories, if that is what they desire, and that transition supports should be provided

- Desire for industries located on First Nation territory to secure partnerships with the community

- First Nations with territory located on wild salmon spawning grounds want to play a role in oversight

- Desire to co-develop a regulatory oversight system that would include First Nations in a tripartite process with the federal and provincial governments

- The Department should engage in government-to-government discussions

- The Department should increase the recognition of modern treaties and associated governance structures

- The proposed timelines for engagement on the transition plan are too short and not compatible with conducting meaningful consultation

- Desire for UNDRIP to be better recognized and implemented in the transition plan and that free, prior, and informed consent from all First Nations whose rights are impacted should be obtained

- Desire to incorporate Indigenous-led science and traditional practices in aquaculture management and decision-making, and for Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers to be more involved in aquaculture management and decision-making

- Desire for funding to help build local capacity to undertake research and monitoring to support informed decisions on aquaculture management

- The decline of wild salmon - which have significant importance to Indigenous culture, traditional teachings, whole ecosystems, and food security - is in part due to open-net pens and a desire for the Government of Canada to compensate First Nations for having to purchase salmon from elsewhere for food, social, and ceremonial purposes as a result of low salmon returns in recent years

- Interest in habitat restoration and salmon enhancement programs, using Indigenous science and western science

Growth in B.C. sustainable aquaculture innovation

We have heard:

- Interest in opportunities to advance semi-closed, closed, and land-based technologies

- Land-based technology requires significant investments due to high startup costs

- Interest in a Centre of Expertise with a focus on First Nation-led science

- Interest in Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture

Marine finfish aquaculture industry

Marine finfish aquaculture industry

Participants from the marine finfish aquaculture industry provided relatively unanimous perspectives on a transition plan. Participants shared that the industry has been innovating continuously, especially since the mandate on developing a responsible plan to transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture in coastal B.C. was first announced in 2019. Participants noted that the innovation and sustainable practices that have already been adopted should be considered as the first steps in a transition. Participants shared that food security and domestic supply is at the top of public concerns during these times of economic and global instability. Additionally, participants identified that Canada has a responsibility to grow its sustainable aquaculture production, specifically with the threat of climate change. Participants suggested that growth in jobs and opportunities for coastal and Indigenous communities could be a measure of success of a transition plan.

Among the marine finfish aquaculture industry, a number of opinions were shared. The following represent points raised by one or more participants.

Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture

We have heard:

- Desire for licensed facilities located on First Nation territories to secure partnerships with the community

- Support for area-based approaches to aquaculture management

- Interest in developmental licences, enhanced performance licences, and/or longer licences to ensure business stability to innovate

- Industry should be given recognition for the innovation and sustainable practices that have been implemented since the mandate to transition from open-net pens was first announced in 2019

- Interest in collaboratively developing measurable, meaningful metrics that demonstrate minimization or elimination of interactions

- Interest in a scorecard or an index of metrics that would cover environmental, fish health, and social considerations for licence holders

- Concerns that a goal of “progressively minimizing or eliminating” interactions means that there may be a requirement to continue to change technologies over time and cause a loss in investment over time

- Transition timelines need to account for the time required for innovation processes, or experimental failures

- There is a need to consider that regulatory streamlining and new technologies may conflict with other regulations

- Desire for science, climate change, and social science to be at the forefront of a transition plan and given equal weight to technological advancements

- Questions about how the transition plan will apply to finfish aquaculture of species other than Atlantic salmon

Trust and transparency

We have heard:

- The Department and the Minister could improve communication on departmental science and the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) process, and show support for the integrity of the CSAS process

- Interest in implementing a communications team/plan focused on delivering science communication

- Interest in enhancing First Nation guardian programs

- Interest in a scorecard to increase trust and transparency in the industry

- Terminology used in the discussion framework needs clarity

Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships

We have heard:

- Support for maintaining and further building First Nation partnerships, and concerns that partnerships will be affected and communities will face significant negative impacts if licences are not renewed

- Interest in embracing Indigenous values, incorporating Indigenous science, and enhancing First Nation guardian programs

- Willingness to increase engagement with Indigenous communities from outside the core territory where they operate at the discretion of the First Nations with whom they have agreements

Growth in B.C. sustainable aquaculture innovation

We have heard:

- Profitability and security of the industry must be restored before incentives to innovate would be effective

- Support for a whole-of-government approach for attracting investment in the industry

- Investments in innovative practices and technology, which relate to other federal government priorities, such as the Climate Change Plan and Blue Economy Strategy, need to be considered

- Climate impacts of alternative technologies need to be assessed and considered in a transition plan

- Existing infrastructure (e.g., energy, transportation, telecommunications) in coastal B.C. is limited and there is insufficient support for growth in land-based and other alternative technology

- Regulatory barriers and multi-jurisdictional licensing processes are other significant challenges to adopting land-based or other alternative technologies

- Access to broodstock and genetic material is not wildly available and would become extremely difficult to obtain if the open-net pen industry was phased out

- Interest in a Centre of Expertise

- New policies should allow for non-technological innovations such as vaccines and animal husbandry

- The achievement of sustainable growth of the sector is reliant on the development of a comprehensive and centralized mandate to sustainably grow seafood production capacity in B.C.

- The Government of Canada should formally separate sector development responsibility from DFO and move it to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- Interest in Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture

Ancillary and land-based industries

Ancillary and land-based industries

Participants from the ancillary and land-based industries articulated many perspectives on a transition plan. Participants expressed a desire for climate change considerations to be emphasized and for improving public support and acceptance of the sector. Participants shared that business certainty and stability is critical in order to develop, trial, and adopt new technologies.

Among the ancillary and land-based industries, a number of opinions were shared. The following represent points raised by one or more participants.

Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture

We have heard:

- Desire for developmental licences, enhanced performance licences, and/or longer licences to ensure business stability to innovate

- Desire for a whole-of-government approach to aquaculture transition and management

- Desire for licences to have thresholds and when a company meets that threshold, they could apply for more biomass (e.g., Norway’s green light system)

- Interest in hybrid systems where post-smolts would spend less time in the ocean

- Desire for science, climate change, and social science to be at the forefront of the transition plan and given equal weight to technological advancements

- Concerns that the transition process is a politically driven decision and not based on risk or science

- Frustration around the potential outcomes of the transition plan (e.g., it is a moving target that industry will always be working towards)

- Interest in a certification of infrastructure to be used as a metric in the transition plan

- Interest in a metric for sea lice that is the same for cultured fish as it is in the wild

- Interest in a scorecard or index that could be part of the industry’s social licence (e.g., industry gains points if they are working with the local First Nations and doing salmon enhancement)

Trust and transparency

We have heard:

- Interest in informing the public about the aquaculture industry in order to increase trust, transparency, and enhance public acceptance of the sector

Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships

We have heard:

- Interest in increasing First Nation guardian programs for monitoring, reporting, and compliance

Growth in B.C. sustainable aquaculture innovation

We have heard:

- Desire for more climate change considerations and assessing the climate change impacts of alternative technologies, including the greenhouse gas emissions of land-based technology

- Interest in a virtual Centre of Expertise

- Interest in the Discovery Islands to be used as an area to trial new technologies since it is in close proximity to shops, power, and supports

- Interest in departmental funding to provide support for the sector, and that current funding lacks national application, consistency, and stability for longer-term confidence and growth

- Perspectives that smaller companies may not have the capacity and resources to trial innovative technologies and may be left behind

- The Government of Canada should formally separate sector development responsibility from DFO and move it to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Local governments

Local governments

Participants from local governments expressed a range of perspectives on a transition plan. Some participants stated support for area-based aquaculture management that would include First Nations and local governments and a desire for the Government of Canada to support communities and workers through a transition. Some participants called for a phase out of all open-net pen salmon aquaculture in B.C.

Among local government participants, a number of opinions were shared. The following represent points raised by one or more participants.

Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture

We have heard:

- Desire for licensed facilities located on First Nation territories to secure partnerships with the community

- Support for area-based aquaculture management that would include First Nations and local governments

- Views that the mandate was understood as a removal of all open-net pens by 2025 and concerns that this target will not be met

- Desire for the Government of Canada to provide economic support for communities and workers through a transition

- Interest in an aquaculture licence buyback program to be included in a transition plan

Trust and transparency

We have heard:

- Interest in third-party monitoring to improve trust and transparency

- Desire for better communication of science and how science translates into policy and decision-making, including more plain language information to be shared with the public

- Desire for the Government of Canada to formally separate sector development responsibility from DFO and move it to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships

We have heard:

- Desire for reconciliation to be a top priority of a transition plan

Growth in B.C. sustainable aquaculture innovation

We have heard:

- Desire for a Centre of Expertise to be located in a coastal community, comprised of interdisciplinary members, and focused on all types of aquaculture

- Desire for significant investment to be able to initiate a Centre of Expertise

- Desire for understanding and incorporating Canada’s blue economy into a transition plan

- Desire for Government of Canada funding to incentivize a transition, which would include support for workers, such as re-training programs

- Interest in engaging with training institutions to identify the need for workforce training and safety programs across the industry

- Interest in training programs to integrate Indigenous knowledge and traditional practices

- Concerns with the industry’s ability to invest in local communities during a time of business uncertainty

- Interest in opportunities for marine plant and shellfish aquaculture

- Concerns with logistical and siting considerations for land-based facilities, including issues with local infrastructure, sewage management, and power

- Concerns with a lack of housing in rural communities, which can cause labour shortages for the aquaculture industry

- Desire for land-based facilities to have adequate monitoring in place (e.g., monitoring of water released)

Environmental groups

Environmental groups

Participants from environmental groups articulated many perspectives on a transition plan. Participants expressed a desire for a target of zero interactions between cultured and wild salmon and for a transition to land-based aquaculture. Participants shared concerns regarding departmental science and the CSAS process, and expressed interest in establishing an independent science review process.

Among environmental groups, a number of opinions were shared. The following represent points raised by one or more participants.

Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture

We have heard:

- Desire for a target of zero interactions between cultured and wild salmon in order to ensure the protection of wild salmon

- Desire for the removal of all marine-based salmon aquaculture facilities and only permitting land-based salmon aquaculture

- Desire for the indicator of success for the transition plan to be all open-net pens out of the water by 2025

- Views that the mandate was understood as a removal of all open-net pens by 2025 and concerns that this target will not be met

- Perspectives that the risks posed by open-net pens on the health of wild salmon are too high to allow for progressive minimization of impacts

- Support for area-based aquaculture management (but not to extend a transition)

- Perspectives that the Government of Canada should provide economic support for Indigenous communities to transition to other economic opportunities

- Desire for industry to participate in wild salmon monitoring and enhancement programs

- Perspectives that a developmental licence could be obtained if industry provides a plan to move towards fully closed-containment by the end of their licence (administered one time only), but that if the complete elimination of interactions between cultured and wild salmon was not reached, then industry would need to transition immediately to land-based technology or stop production completely

- Interest in adopting international standards and looking to Norway for examples of their environmental standards, research and development processes, tax incentives mechanisms, and monitoring tools

Trust and transparency

We have heard:

- Interest in independent monitoring of wild salmon and third-party observers to validate reporting

- Desire for clear public reporting of aquaculture activities and clear demonstration of how feedback is included in management and decision-making to increase trust and transparency

- Desire for the Department to increase the accessibility and availability of data that can be analyzed by independent researchers

- Concerns that departmental science is not being inclusive of all scientific research, cumulative effects assessment, or Indigenous science and knowledge

- Environmental groups are not in agreement with DFO and CSAS findings regarding the risks of open-net pens to wild salmon

- Views that the CSAS and departmental science processes could be reviewed to ensure that there are no conflicts of interest, industry bias, and that a precautionary approach is adopted

- Interest in the establishment of an independent science review process that could include an independent science advice board that would provide science advice to the Department and the Minister

- Interest in enhanced enforcement of metrics and consequences in the event of non-compliance

- Desire for the Department to develop interactive and publicly available maps of all open-net pens. These could include information on facilities and their compliance to licence conditions, sea lice reporting, etc.

Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships

We have heard:

- Interest in collaborative monitoring programs to be developed between environmental groups and First Nations

- Desire for establishing metrics that meet or exceed the current standards of B.C. Indigenous partnerships

- Support for industry to secure First Nation partnerships from those within whose territories their licensed facility is located if there is to be any continuation of operations

Growth in B.C. sustainable aquaculture innovation

We have heard:

- Desire for financing mechanisms such as an innovation fund, tax credits, or government guarantees to support the industry to innovate

Researchers and academics

Researchers and academics

Researchers and academics shared a range of perspectives on a transition plan. Some participants expressed a desire for the removal of all marine-based salmon aquaculture facilities and only permitting land-based production. Some participants expressed support for area-based aquaculture management and for requiring industry to secure First Nation partnerships from those within whose territories the licensed facility is located. Participants articulated concerns with DFO’s science review process, science advice, and/or science communication.

Among the research and academic participants, a number of opinions were shared. The following represent points raised by one or more participants.

Transition from open-net pen salmon aquaculture

We have heard:

- Desire for a target of zero interactions between cultured and wild salmon and perspectives that this is not possible with open-net pens in the water

- Desire for the removal of all marine-based salmon aquaculture and only permitting land-based salmon aquaculture

- Views that the mandate was understood as a removal of all open-net pens by 2025 and concerns that this target will not be met

- Concerns that progressively minimizing interactions suggest status quo, and that this will not solve the current crisis of salmon decline

- Support for Indigenous self-determination in their own territories

- Support for requiring industry to secure First Nation partnerships from those within whose territories the licensed facility is located

- Support for conditions of licence to be set in agreement with regulators, First Nations within whose traditional territory the facility is located, and industry

- Support for area-based aquaculture management and interest in area-based production planning, for which the unit of management could consider social, economic, political, and ecosystem science considerations to determine the level of acceptable risk for aquaculture practices in that region

- Concerns that metrics cannot be developed until the outcome and timeline of a transition plan are defined, or until the level of acceptable risk for different regions is determined

- Interest in collaboratively developing metrics

- Perspective that area-based aquaculture management provides a sensible approach to integrating ecologically unique areas

Trust and transparency

We have heard:

- Disagreement with departmental science pertaining to aquaculture and wild salmon risks, and views that there is other scientific evidence that shows that open-net pens have negative impacts to wild salmon

- Views that the CSAS and departmental science processes could be reviewed to ensure that there are no conflicts of interest, industry bias, and that a precautionary approach is adopted

- Interest in the implementation of an independent science review board that would provide science advice to the department and to the Minister

- Interest in a new science dissemination body to provide science advice to area management groups, and to help inform the public and local decision-makers of the available science concerning aquaculture, and that the group should span scientific disciplines and not include departmental staff

- Desire for more raw data to be made publicly available, so that independent researchers can analyze and interpret data

- Desire for improved communication of departmental science, the CSAS process, and externally contracted reports

- Interest in monitoring and reporting to be done in an all-party collaboration with multi-party oversight

- Interest in monitoring and reporting to be done with standardized and accredited methods of evaluation, and that data must be robust, repeatable, and internationally recognized and approved

Reconciliation and Indigenous partnerships

We have heard:

- Support for Indigenous self-determination in territories within which open-net pens are situated

- Support for requiring industry to secure First Nation partnerships from those within whose territories their licensed facility is located

- Support for conditions of licence to be set in agreement with regulators, First Nations within whose traditional territory the facility is located, and industry

- Interest in the Government of Canada to provide support for First Nations to transition to other economic opportunities

- Interest in the integration of traditional knowledge and collaboration with Guardian programs

Growth in B.C. sustainable aquaculture innovation

We have heard:

- Perspectives that land-based salmon aquaculture is the only alternative technology that can reach a desired target of zero interactions

Annex B: Summary of survey findings

An online survey was launched as part of the external engagement in the development of the open-net pen transition plan.

The survey was originally launched on August 11, 2022. Based on feedback received, the survey was paused on September 6, 2022 in order to provide greater clarity. The revised survey was relaunched on September 28, 2022. Two hundred and ninety (290) submissions were received prior to September 6, 2022. These results have been taken into consideration and given equal weight to those received after the re-publication. A total of 2,890 responses were received before the survey closed on October 27, 2022.

Overall, 70% of survey respondents supported a transition away from any marine salmon aquaculture to a sustainable land-based sector. Of those who support a transition away from marine aquaculture:

- Policy and management tools to progressively reduce or eliminate interactions between cultured and wild salmon were viewed as ineffective

- There is a desire to focus transition supports into other sectors not related to aquaculture

- A land-based system, such as a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) was viewed as the highest priority in advancing innovation in the open-net pen transition plan

Twenty-two percent (22%) of online survey respondents supported a transition to sustainable and economically viable salmon aquaculture industry which drives innovation and supports the use of new technology. Of those who support this type of transition:

- Policy and management tools to progressively reduce or eliminate interactions between cultured and wild salmon were viewed as effective

- Area-based aquaculture management was viewed as the most effective management tool

- There is emphasized focus on a transition which supports and maintains the capacity for an aquaculture economy in B.C.

- In general, survey respondents that indicated themselves as Industry Representatives support a transition to sustainable and economically viable salmon aquaculture industry which drives innovation and supports the use of new technology

Eight percent (8%) of survey respondents supported a reduced aquaculture sector that transitions coastal economies to other sectors, such as tourism. Of those who support this type of transition:

- Policy and management tools to progressively reduce or eliminate interactions between cultured and wild salmon were viewed as ineffective

- There is a desire to focus economic supports into other sectors not related to aquaculture

- A land-based system, such as a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) is viewed as the highest priority in advancing innovation in the open-net pen transition

- There is a desire to promote collaboration amongst industry through an aquaculture “supercluster”

- Workforce training and upskilling were viewed as very important

Overall, survey respondents expressed that enhancing transparency of the scientific review process within the Department to confirm that robust information and assessment informs decision-making is the most important approach to improve trust and transparency. Regular public accountability related to a transition plan and enhanced roles for First Nations were also viewed as very important.

Survey respondents attributed equal priority to the following proposals to support reconciliation with First Nations in an open-net pen transition plan:

- A requirement for salmon companies to secure coastal First Nation partnerships from those within whose territories their licensed facility is located

- Create aquaculture management areas that reflect the input and interest of Indigenous peoples

- Enhance opportunities for First Nation partnerships for monitoring, stewardship/guardianship programs and research and development

- Support enhanced Indigenous knowledge and science contributions to aquaculture management

Survey data is available upon request.

Annex C: Proposed metrics to measure success

A variety of stakeholder and partner groups shared views on metrics that could potentially demonstrate success of a transition plan.

Social, cultural and economic

- Collaboration with local First Nations

- Participation in wild salmon protection or enhancement activities

- Social, cultural, and economic wellbeing of Indigenous and non-Indigenous coastal communities where salmon aquaculture contributes to the local/regional economy

- B.C. salmon aquaculture’s contribution to Canada’s blue economy and food security

Sustainability

- Sustainable certification of facilities, which would support climate resilient and energy efficient operations

- Carbon impact of the industry and the sector’s capacity to take action on climate change

Interaction

- Zero interactions between wild and cultured salmon

- Reduction in escapes

- Enhanced wild fish assessments

- Interaction with marine mammals

Sea lice

- Number of sea lice on cultured salmon could be the same as background levels on wild salmon, and that a ‘zero’ sea lice metric would be unrealistic to achieve and may reflect increased treatments rather than reduced interactions

- Stricter sea lice motile threshold and stricter enforcement

- Reductions in sea lice per fish or per farm

Disease, pathogens, and algal blooms

- Water parameters including eDNA (pathogens or plankton)

- Monitoring of juvenile wild salmon for signs of infection near open-net pens and away from open-net pens

- New metrics related to Piscine Orthoreovirus or Tenacibaculum maritimum

Wild salmon/environmental monitoring

- Monitoring of wild salmon returns during spawning periods

- Measures of wild salmon exposure and exposure duration to open-net pens

- Wild salmon health and welfare near and far from open-net pens

- Enhanced fish health parameters (e.g., independent lab and testing at internationally accredited facilities, sharing of historic and ongoing survival to harvest, reporting of treatments, etc.)

- Benthic impacts (e.g., develop a more efficient and meaningful mechanism to participate in monitoring, access to lab results, development of eDNA use in surveys, in-depth review and determination of cumulative effects and long-term impacts post-decommissioning, etc.)

General

- Metrics that meet or exceed the current standards of First Nation partners

- Post/larger smolt entry (e.g., participation of evaluations of efficacy/cost effectiveness, development of new health markers, ecosystem and climate change impact on smolt health status, etc.)

- Date modified: