Comparative analysis of commercial fisheries policies and regulations on Canada’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts

Prepared by Michael Gardner, Gardner Pinfold Consultants Inc. Halifax, January 2021

Table of contents

- Disclaimer

- 1 Background

- 2 Management policies in the Atlantic and Pacific fisheries

- 3 Applying Atlantic fisheries policies in the Pacific Region

- 3.1 Atlantic policies designed to support independent harvesters

- 3.2 Pacific fisheries stakeholder perspectives on implementing Atlantic policies

- 3.3 Lessons learned from implementing PIIFCAF policies

- 3.4 Changes to Pacific fisheries management to implement Atlantic-type policies

- 3.5 Administrative and enforcement measures

- Footnotes

Disclaimer

In preparing this report, the consultant benefited from discussions with DFO officials and industry representatives and wishes to thank them for their input.

Notwithstanding this assistance, the analysis, observations and conclusions are those of the consultant alone. The consultant also takes responsibility for any errors or omissions.

1. Background

1.1 Purpose and objectives

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans (the “Committee”) in 2019 conducted a study to examine the regulation of the Pacific coast fisheries. This initiative came in response to testimony concerning quota licencing policy heard by the Committee in 2018 during its consideration of Bill C-68 (An Act to amend the Fisheries Act). In its study, the Committee set out to examine:

"… the regulation of the West Coast fisheries, specifically in relation to fishing licences, quotas, and owner operator and fleet separation policies, in order to evaluate the impact of the current regime on fisheries management outcomes, the distribution of economic benefits generated by the industry and the aspirations of fishers and their communities, and to provide the government with options and recommendations to improve those outcomes."

In its ensuing report, West Coast Fisheries: Sharing Risks and Benefits, the Committee made 20 recommendations. They are intended to address several shortcomings: the lack of transparency of the fisheries management framework; the barriers new harvesters face in entering the fisheries; the marginal viability of many fishing enterprises; and, the inequitable sharing of risks and benefits across industry participants.

The purpose of this study is to provide a response to the Committee’s Recommendation 6:

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada develop a comparative analysis of the East Coast and West Coast fisheries in regard to regulations with a view to devising policy that would level the playing field for independent British Columbia fishers.

The main objective of the report is to compare fisheries policies and regulations in effect on Canada’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts and identify provisions that have the potential to provide additional support to independent harvesters in British Columbia.

1.2 Scope

To meet these objectives, the study incorporates findings from the following:

- review fisheries policies and regulations in effect on Canada’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts and identify provisions intended to ensure the benefits derived from fish harvesting flow to active fishers and communities and provisions that encourage a fair distribution of benefits among those involved in the fishery;

- identify factors that contributed to different landed value trends in Atlantic and Pacific coast fisheries between 2000 and 2015 noted in the Committee report and the influence of fisheries policies and regulations on these trends;

- develop a list of fisheries that are covered by the Policy for Preserving the Independence of the Inshore Fleet in Canada’s Atlantic Fisheries (PIIFCAF), and a list of Atlantic fisheries that are exempt from PIIFCAF and describe the rationale for each exemption;

- identify other Atlantic policies and regulations that have the potential to provide additional support to independent fish harvesters in BC;

- highlight lessons learned from experience in Atlantic fisheries that could inform the consideration of applying Atlantic-type fisheries policies and regulations in BC, and identify specific changes to the management of Pacific fisheries that would need to be made to implement Atlantic-type fisheries policies and regulations in BC; and,

- identify administrative and enforcement measures that would be required to implement Atlantic- type fisheries policies and regulations in BC.

The perspectives of First Nations, major stakeholders in the Pacific fisheries, are not covered in this review. This is for two reasons: first, because this report focusses mainly on Atlantic fisheries policies and regulations emerging from PIIFCAF, whose provisions apply to commercial harvesters but not to First Nations in Atlantic Canada; second, and arguably more importantly, because the matter of First Nations’ involvement in the fisheries on both coasts, including the applicable policy and regulatory framework, would require its own study rather than a cursory review.

2. Management policies in the Atlantic and Pacific fisheries

2.1 Statistical overview

Before delving into the dry details of fisheries management policies on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts it may be useful to provide a broad overview of the state of the respective fisheries using key statistics. While these are helpful in highlighting differences in structure and scale, some interpretation is needed to gain insight into how they contributed to the development of fisheries policy on the respective coasts. A key point to note is that the Atlantic fisheries are divided into inshore (<65’) and offshore (>100’) fleet sectors (with a handful of midshore vessels in between). This report focuses on the inshore sector because of its similarities to the Pacific fisheries in terms of vessel size and gear types.

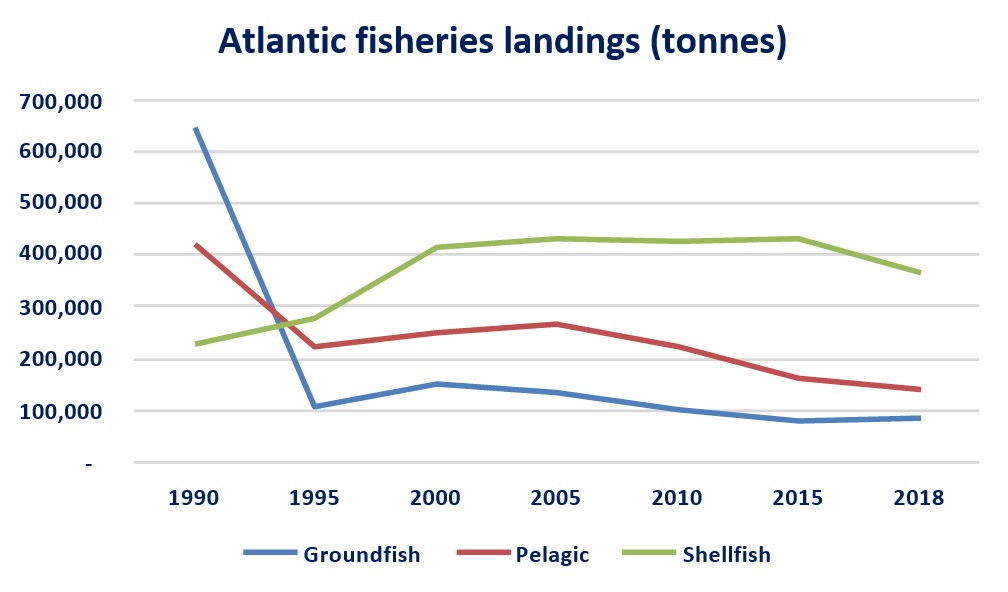

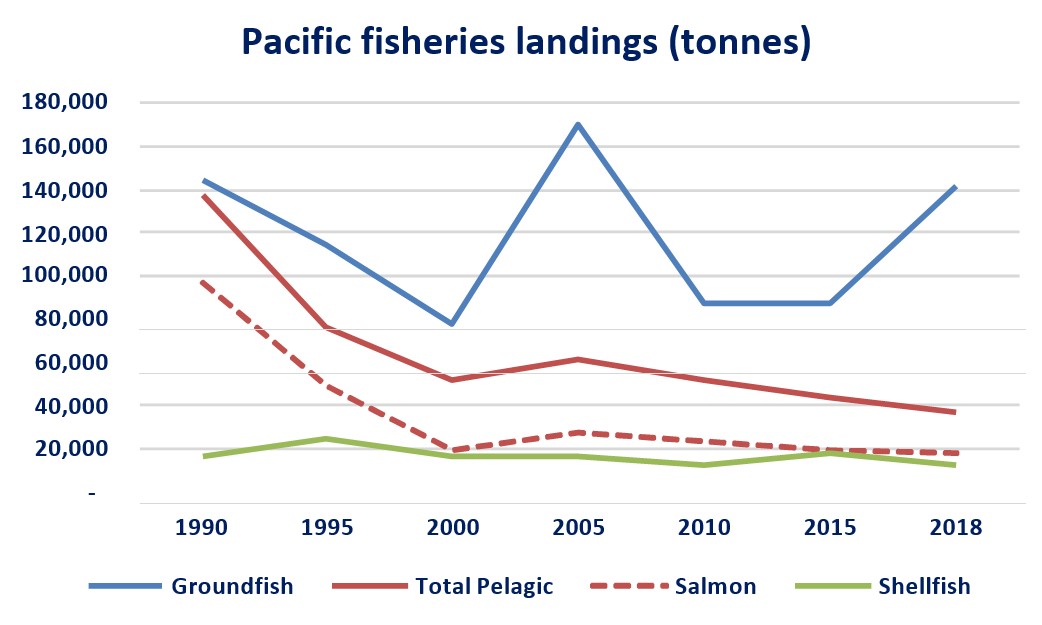

The charts below set out high-level statistics illustrating the differences in the scale of the fisheries. Harvesters in the Pacific fisheries landed less than one-quarter the tonnage of their Atlantic counterparts in 1990; by 2018, they landed one-third as much. Atlantic landings declined by over half, from 1.3 million t in 1990 (due mainly to the collapse of groundfish stocks) to just under 600,000 t in 2018. Pacific landings also declined in the aggregate over this period, but by proportionately less: from about 300,000 t to just under 200,000 t. The wide swings in groundfish landings in the Pacific was due almost entirely to a periodic strong hake fishery.

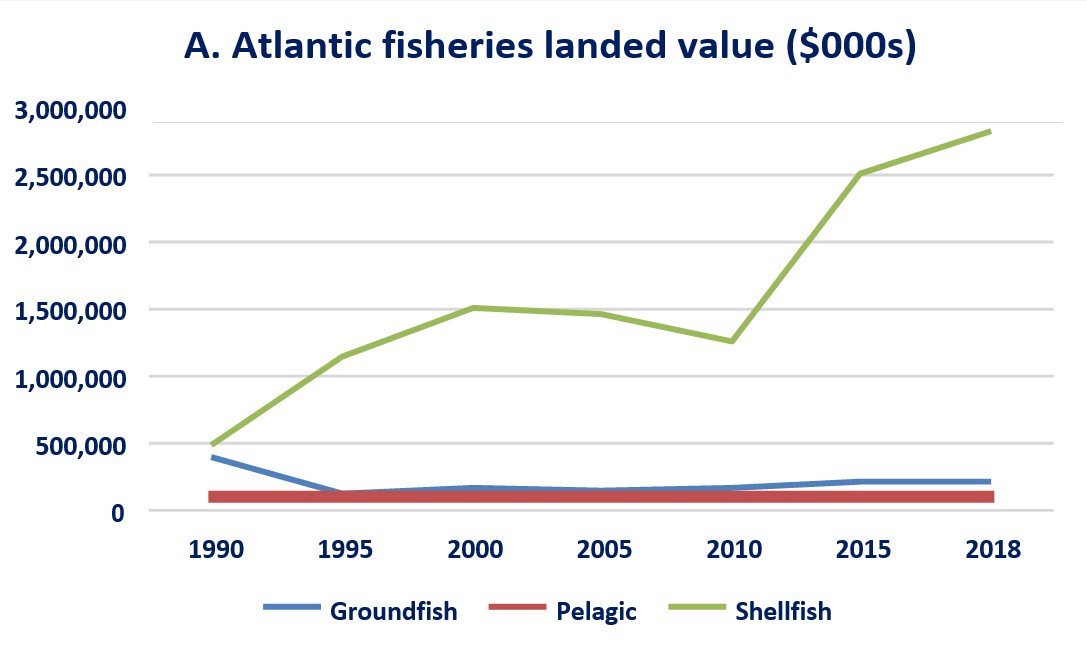

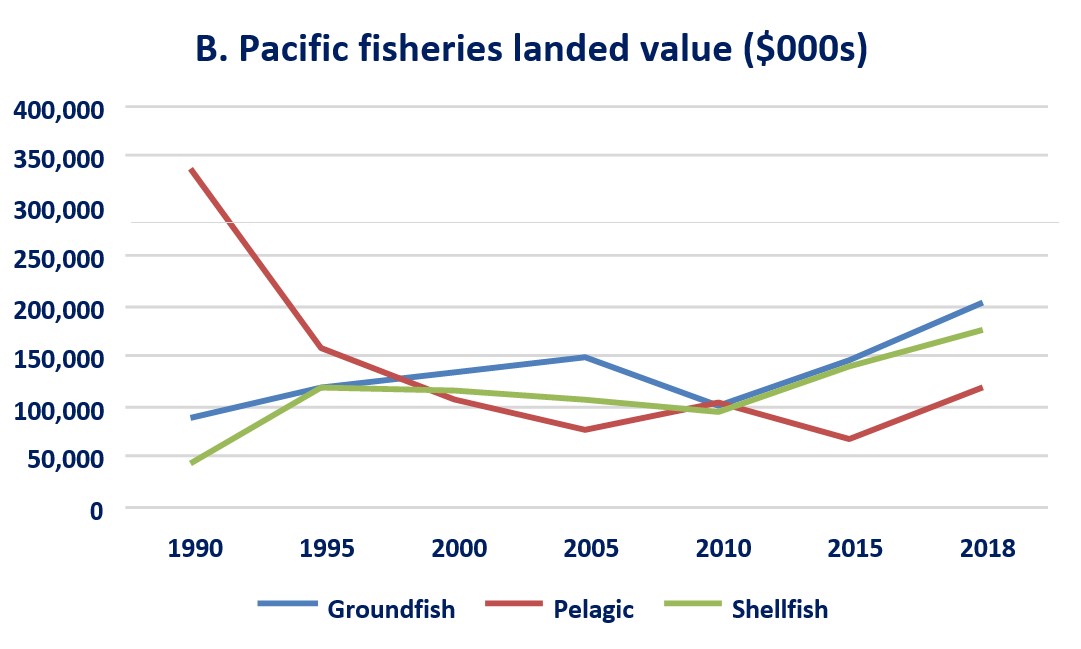

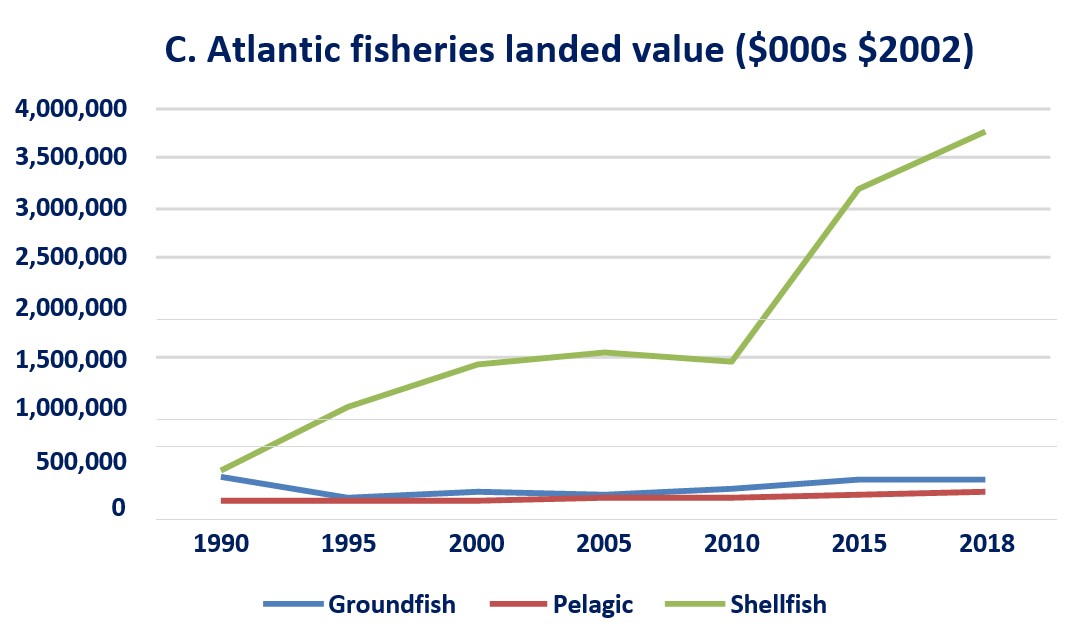

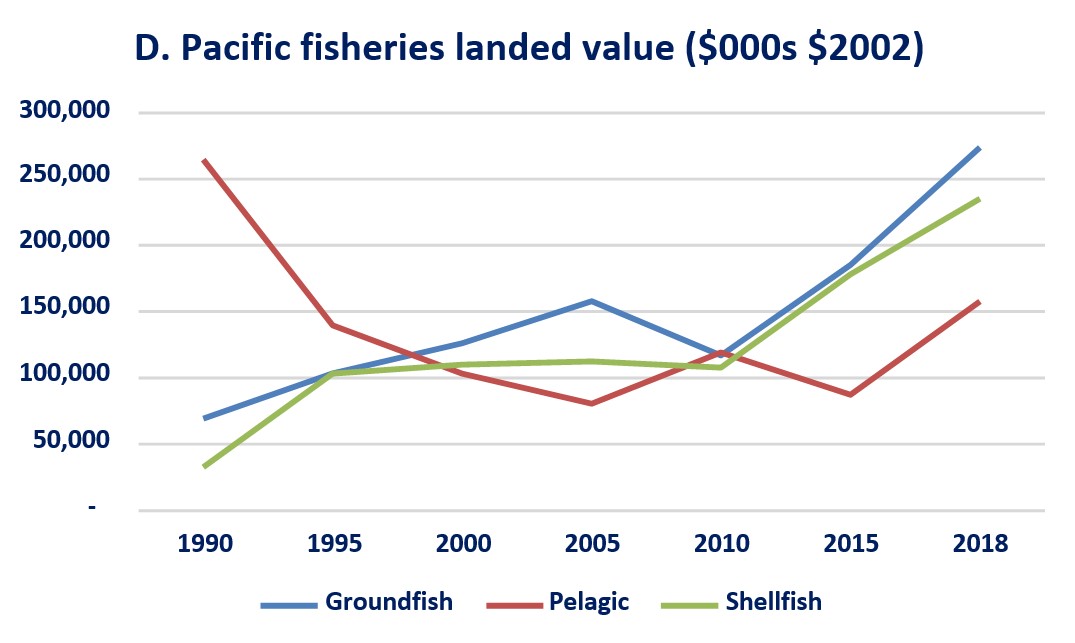

Shellfish landings doubled on the Atlantic, while remaining fairly stable on the Pacific. Pelagic landings dropped by more than half on both coasts, with a serious impact on salmon fleets in the Pacific fisheries. The impact of shifting species abundance comes into sharper relief when considered in terms of value. Total landed value in the Atlantic fisheries increased by a factor of 3.3 (current dollars) between 1990 and 2018, rising from $950 million to $3.2 billion (Chart 2A and 2B). By contrast, landed value in the Pacific fisheries increased by a factor of 1.1, rising from $470 to $500 million.

Chart 1: Atlantic and Pacific fisheries landings, 1990-2018

Source: DFO

Source: DFO

Chart 2: Atlantic and Pacific fisheries landed value, 1990-2018

Source: DFO, Statistics Canada

Source: DFO, Statistics Canada

Source: DFO, Statistics Canada

Source: DFO, Statistics Canada

Chart 2C and 2D illustrate the impact over time of removing the effects of inflation on landed value. Note the five-fold differences in the scale of values between Charts 2A and 2C, and 2B and 2D. By removing inflation (using $2002), landed value pre-2002 is higher and post-2002 lower, more accurately reflecting their relative values in real terms. While the general shape of the curves does not change, removing inflation provides a more accurate indication of real change over time: total landed value in the Atlantic fisheries increased by a factor of 2.0 between 1990 and 2018 (Chart 2C), while landed value in the Pacific fisheries declined by almost 40% (Chart 2D).

For the Atlantic fisheries, the change in species mix over the past 30 years caused a marked transformation from a relatively low value, high employment groundfish-dependent industry to a high value, low employment shellfish dependent industry (Chart 2A/2C). This is accounted for mainly by lobster (>99% caught by inshore vessels) and snow crab (caught exclusively by the inshore sector), and to a lesser extent by shrimp and scallop (caught by inshore and offshore vessels).Footnote 1 Certainly, favourable environmental conditions played a key role in explaining the rising shellfish abundance (and, coupled with overfishing, the decline in groundfish). But sharply rising lobster prices with the development of the Chinese market was a major factor in driving the growth in value since 2010.

The transformation of the Pacific fisheries has been marked mainly by the decline in salmon stocks as well as the herring roe fishery, whose combined value (nominal dollars) dropped by about two-thirds since 1990 ($336 to $104 million). The decline in landings has been offset to some extent by rising prices for key species in the past few years (mainly crab, shrimp and halibut). This recent market impact is evident by comparing landings in Chart 1 with landed value, especially the constant dollar impact in Chart 2D.

The changes in landings depicted in Charts 1 and 2, occurred against a backdrop of changes in industry participation on both coasts, particularly the declining number of harvesters and vessels (Table 1).Footnote 2

Table 1: Atlantic and Pacific fisheries key statistics, 2000 and 2018

| - | Atlantic | Pacific | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 2000 | 2018 | % change | 2000 | 2018 | % change |

| Vessels (#) | 20,200 | 15,946 | -21% | 3,446 | 2,351 | -32% |

| Licences (#) | 76,589 | 75,755 | -1% | 7,834 | 6,192 | -21% |

| Licence-holders (#) | 11,987 | 9,854 | -18% | 8,760 | 5,462 | -38% |

| Landings (tonnes) | 855,305 | 593,249 | -31% | 147,782 | 191,227 | 29% |

| Landed value ($000s 2002=100) | ||||||

| Total | 1,677,665 | 4,214,000 | 151% | 339,352 | 665,873 | 96% |

| Inshore only | 1,238,334 | 3,340,318 | 170% | - | - | - |

| Value/licence-holder ($ 2002=100) | ||||||

| Total | 139,957 | 427,644 | 206% | 38,739 | 121,910 | 215% |

| Inshore only | 103,306 | 338,981 | 228% | - | - | - |

Table 1: credits

Vessels: Atlantic includes only inshore; Pacific includes all.

Licences: Atlantic includes total species-specific licences; Pacific includes vessel- and party-based.

Licence-holders: Atlantic includes Core and Independent Core; Pacific includes all. Crew numbers not included

Landings: live weight. Atlantic total includes inshore and offshore (data source does not separate). Inshore estimated at 50% of total in 2018. Landed value: Atlantic total includes inshore and offshore (sector data not available from published DFO data).

Inshore only: split estimated by the consultant using constant ratios (by species) of landed value for species harvested by both sectors. Value/licence-holder ($): derived by dividing inshore landed value by the number of inshore licence-holders.

The number of licence-holders, vessels and licences has declined in both Regions since 2000, with greater declines in the Pacific for each indicator. Against the backdrop of reduced industry activity, the value of landings (in constant 2002 dollars) increased by 28% in Atlantic and remained essentially unchanged in Pacific. But the more significant indicator is landed value per licence-holder; this increased overall by 56% in the Atlantic fisheries vs. 61% in Pacific. The percentage increase in landed value/licence-holder for the Atlantic inshore sector alone rose by 68%, due largely to the substantial increase in the value of the lobster and snow crab fisheries after 2000.Footnote 3

What inferences can be drawn from these data? The House of Commons Standing Committee, drawing on a report by Ecotrust Canada and the T. Buck Suzuki Environmental Foundation, noted that “…data suggested no growth in British Columbia’s fishery while both Atlantic Canadian and Alaskan fisheries saw significant growth in their landed values”.Footnote 4 The Ecotrust report itself notes, “A review of the catch landed in BC over the past fifteen years shows a decline in value and a steady trend in volume.

Conversely, the volume in Atlantic fisheries has declined but they have seen an increase in overall value. It is striking that this greater value realized for a declining catch is something BC has not managed to achieve.”Footnote 5

Given its importance in the overall narrative, the Standing Committee included the chart from the Ecotrust/T. Buck Suzuki report in its own report. It is reproduced below.

Figure 1—Landed Volumes and Values from 2000 to 2015 Relative to 2000

Source: Ecotrust Canada and T. Buck Suzuki Environmental Foundation, Just Transactions, Just Transitions: Towards Truly Sustainable Fisheries in British Columbia, 21 December 2018, p. 25.

This chart (Figure 1) is in the nature of an index, with annual values expressed as a percentage of a base year value, in this case that of 2000. For the years in question (2000-2015) it relies on the same DFO Regional landings data used in producing Charts 1 and 2A/2B, above. In other words, if annual data for the 2000-2015 period were used and indexed to 2000, the latter would look identical to BC and Atlantic in Figure 1, above. [To provide greater perspective, Chart 1 (above) takes the data back to the 1990s, when a collapse of Atlantic groundfish and Pacific salmon stocks caused landings and landed values on both coasts to decline precipitously.] Removing the impact of inflation (a form of indexing) provides a more accurate of measure of change over time. In real terms, then, Pacific fisheries total landed value has almost doubled between 2000 and 2018 (Table 1, above). Due to the decline in licence-holders, the average landed value per licence-holder increased by a factor (±60%) comparable to that of Atlantic inshore harvesters (Table 1, above).

A key point in all this is that these aggregate data are of limited value in trying to tease out the impact of differences in fisheries policy on the income of harvesters in Atlantic and Pacific. The strong performance of the Atlantic fisheries may be explained primarily by two factors: first, by broad-scale environmental and ecosystem change that contributed to the collapse of groundfish stocks while supporting a substantial increase in abundance of three intrinsically more valuable crustacean species (lobster, snow crab and northern shrimp); and second, by a substantial increase in the unit market value of these species in recent years (which flowed through to harvesters in higher shore prices). The BC fishery experienced a similarly devastating decline in abundance of key species (salmon, herring) after 1990, but not the corresponding increase in landings (and value) from other species that would have more than offset the loss (as in the Atlantic).

Moreover, aggregate landings data are of limited value in isolating policy impacts without knowing more about how shore prices are set, and how the gross value of landings is distributed amongst the various interest holders in the licence. In both the Atlantic and Pacific fisheries, boat prices tend to be closely linked to shifts in product markets, either through competitive forces in port markets or collective bargaining. Common to both approaches is a harvesting sector that is well-informed about price movements in product markets and what processors/buyers are actually paying on the shore on any given day. The independence of fleets from processors/buyers plays a key role in sustaining a competitive environment on the Atlantic coast. This does not mean that the processing/buying sector is immune from attempts to act collusively to try to control prices. But such attempts tend not to work because it proves impossible to secure full- or on-going cooperation given the lack of processor/buyer concentration in such key fisheries as lobster and crab. To the extent buyer concentration exists, prices could be expected to be lower than ones that are competitively determined.

The second limiting factor – relying on gross value of landings – presents a problem because this measure may overstate or understate the return to the vessel. If the vessel operator does not hold quota but pays to lease it, for example, then landed value overstates what would be conventionally understood as the revenue accruing to the vessel to cover operating expenses, including crew. Conversely, where supply arrangements with buyers incorporate payments to vessel owners not expressed in shore prices, then returns to the vessel would be understated. Both practices exist to a greater or lesser degree in Atlantic and Pacific fisheries.

2.2 Atlantic fisheries

Policy development since the 1970s

The current rules governing licencing to participate in the Atlantic fisheries began to take shape in the mid-1970s as the industry struggled with the combined effects of declining fish stocks, weak markets, overcapacity and rising fuel costs. The 1976 Policy for Canada’s Commercial Fisheries noted that, “Many of the problems are inherent in the industry’s structure. Too often the fishing industry has been unstable and self-debilitating, prone to crises, and providing an inadequate and nearly always insecure source of income to those who work in it.” (p. 3)

The Policy addressed a range of issues facing the industry and recommended an interventionist strategy to deal with them including a focus on industry reconstruction. It went on to observe that some form of reconstruction is inevitable and that it would come about either in an orderly fashion under government auspices or through the operation of market forces.

“Although commercial fishing has long been a highly regulated activity in Canada, the object of regulation has, with rare exception, been protection of the renewable resource. In other words, fishing has been regulated in the interests of the fish. In the future, it is to be regulated in the interest of the people who depend on the fishing industry. Implicit in this new orientation is more direct intervention by government in controlling the use of fishery resources, from the water to the table...” (p. 5)

As implemented, the interventionist approach involved controls on fishing effort, and also on the ownership structure and operation of fishing and processing enterprises. The objectives were aimed at creating wealth particularly in the inshore harvesting sector and spreading it as widely as possible.

Capacity expansion and effort control

The thrust of the inshore development policy is best summarized by the words of the fisheries minister in 1978:

Measuring the 200-mile limit as a belt from the coast, we must measure its benefits first of all in relation to those living on the coast. When we divide up those few million tons of fish, the coastal communities of inshore and nearshore fishermen must have first claim. ... Instead of starting with an offshore, large vessel development that cuts off future inshore growth, we must build from the independent fleet up and from the coast out. We must give the inshore and nearshore fishermen a greater and an assured amount of fish. As he begins making money, he can move up to vessels that extend his mobility, increase his catches, and lengthen his working season (LeBlanc, 1978, emphasis added).Footnote 6

While it is difficult to reconcile the latter part of this statement with the existing concerns about overcapacity (and the general tone of the 1976 Policy with respect to restructuring), the sentiment reflected in this statement would govern fisheries management and resource sharing on the Atlantic coast for the next decade. It had a major impact on allocation and licensing policy and, in turn, provided an incentive for increased investment in fleet and processing capacity in both the inshore and offshore sectors.

The next several years were marked by sharp conflicts over allocations between the inshore and offshore sectors and within the various inshore gear sectors. Against the backdrop of capacity expansion, this served to destabilize the fishery, worsened the already difficult task of resource management, and by the early-1980s, had effectively undermined Canada’s conservative harvesting strategy. Capacity growth and sector conflicts made it increasingly difficult to set conservative TACs and control catches within the allocations.Footnote 7

A 1981 review of licencing policy endorsed the concept of limited entry while recognizing that without more, it would be unable to constrain capacity growth and fishing effort. Several options for addressing the problem were reviewed including the then novel idea of controls on output (individual quotas) rather than input (vessels and gear). The use of individual quotas was gaining ground amongst fishery managers and academics as a more effective means of promoting economic efficiency. The concept was dismissed in the 1981 licencing policy review as an idea whose time had not yet come (Levelton, 1981). Instead, DFO concentrated on input controls, in particular, vessel replacement restrictions.

Licencing policy took shape in the 1980s, following reviews in 1979 and 1981. These formed the basis of a discussion paper (Commercial Fisheries Licencing Policy for Eastern Canada, 1985), followed by a Proposed Commercial Fisheries Licencing Policy for Eastern Canada in 1988, and culminating in the formal statement of policy in 1989, Commercial Fisheries Licencing Policy for Eastern Canada. With some modifications to address emerging management issues, the 1989 Policy was reissued in 1990 and 1992.

Following Program Review in 1995, the Policy was up-dated in 1996 to reflect different priorities following the collapse of groundfish stocks. Resource sustainability and economic viability continued as overarching goals, but fleet development was dropped in favour of reducing capacity, improving the economic viability of participants, and preventing future growth of capacity.

This change in objectives was important because it signaled a recognition by DFO that actually giving effect to sustainability and viability meant taking action to reduce demands on the resource and expectations about what the fishery could support. To these ends, a buy-back program was implemented and initial steps in the early 1990s to introduce market-based approaches to management (IQs and ITQs) gained wider support.

The Policy also set the groundwork for a different relationship with the fishing industry, one that intended to give the industry more responsibility in operational decisions affecting the fisheries. Key elements of licencing policy that determined industry structure – fleet separation and owner-operator policies – and the competitive behaviour that flowed from that structure were tightened under the 1996 Policy.

Fleet separation

DFO took an important step in the late 1970s in defining industry structure: the introduction of fleet separation. This policy – announced in 1977 and implemented in 1979 – essentially prohibited processing plants from owning and operating inshore fishing vessels. It was introduced to protect the interests of the harvesters, particularly with respect to setting shore prices; DFO's response to a perceived imbalance of power between the processing and harvesting sectors.Footnote 8

As expressed in the 1989 Commercial Licencing Policy, fleet separation policy simply stated that “…new fishing licences for the inshore fishery cannot be issued to companies involved in the processing sector of the industry.” This same wording appears in the 1990 and 1992 editions of the Policy, but the wording changed in the 1996 edition: “…new fishing licences for fisheries where only vessels less than 19.8m (65’) LOA are permitted to be used may not be issued to corporations, including those involved in the processing sector of the industry.”

DFO was prohibiting corporations from being named to the licence, as it was a violation of the owner- operator policy. This practice, though intended to prevent vertical integration, had a negative impact on harvesters who had incorporated to take advantage of tax benefits available to other sectors of the economy. Incorporated harvesters were unable to have their enterprise named to the licence until the implementation of the Policy on the Issuance of Licences to companies came into effect in 2011.Footnote 9 This policy allowed only for a specific type of company to become the licence holder, i.e. a company that was wholly owned by an eligible licence holder.

Fleet separation was intended to maintain a certain industry structure and organize activity in a certain way. Competition for raw material benefitted harvesters, though how much difference the Policy itself made at outset is unclear because it was introduced at a time (1979) when few inshore vessels were owned by processing companies. Few companies saw any advantage in vertical integration. This changed over time as entry into the processing sector increased and competition for raw material intensified as all the major fisheries were subject to limited entry. In other words, the number and scale of buyers increased as the number of sellers remained fixed (or diminished due to buy-out programs or fleet rationalization initiatives). An unintended consequence of the imbalance was that price ceased to have any effect in influencing the timing and quality of fish landings. The role that price plays in these respects in other industries (i.e., rising and falling in response to the interplay of demand and supply, rewarding quality, etc.) is noticeably absent in the Atlantic fisheries.Footnote 10

In these circumstances, processors found themselves in a weak position to respond to shifts in demand from product markets (either with respect to quantity, quality or product form). Because they lacked direct access to the resource, they naturally tried to develop other mechanisms to attract the loyalty of vessels. Plants would provide a wide range of operational and financial services, including loans to finance vessels and secret bonus payments. But regardless of what method they used, they still had to pay the prevailing shore price or risk losing the vessel to a competitor. These measures worked to a point but fell short of the level of security needed to develop effective business plans.Footnote 11

The licence itself gradually became the object of financing (during the late 1980s), as prices of the more valuable licences increased (due to improved resource and market conditions) and as demand increased relative to supply (due initially to limited entry and later to the entry of DFO in the licence market following the Marshall decision). The licence became an object of interest to processors because it provided a more direct and secure avenue to raw material supply.

Conventional financing for the purchase of a licence was a relatively unattractive proposition for traditional lenders because of the restrictive terms of the licence. Section 16 of the Fishery (General) Regulations states that a licence is the property of the Crown and is not transferable. Even though licence holders can request that the licence be transferred to a new recipient, the licence is a privilege granted by DFO and was not considered a tangible asset. Depending on the security demanded by a lender, prior to the Supreme Court ruling in Saulnier (2008)Footnote 12 establishing that licences can be used as collateral for loans, they could provide little or nothing to attach in the event of a default. For most, this restriction tended to rule out access to conventional financing.

By the late 1980s, trust agreements (TA) began to be used as a way to secure financing from within the fishing industry (processing plants and other harvesters). Legal title to the licence remained with the licence-holder, while the beneficial interest in the licence (the use of it) was transferred to the lender/investor by contract (the TA) as a form of security. This skirted the spirit of the law and the policies, but was consistent with its letter, since legal title in the licence remained with the licence- holder as prescribed by regulation. TAs are discussed more detail in the context of the policy for Preserving the Independence of the Inshore Fleet in Canada’s Atlantic Fisheries (PIIFCAF), below.

Owner-operator policy

Licencing had been an important element of fisheries management for decades prior to the modern era of management beginning in the late-1970s. Among the bedrock elements of Atlantic licencing policy for 30 years are the owner-operator provisions. They require the licence-holder to fish the licence issued in their name personally (though substitutes would be permitted under specified conditions) and precluded horizontal concentration by limiting licence holders to one licence per given species. These provisions were introduced at a time when two of the objectives of policy generally were to maximize employment in the fishery (nominally subject to resource conditions) and to ensure equitable access to the resource. Owner-operator became policy in the Atlantic lobster fishery in 1980, spread to other fisheries in ensuing years, and became universal in the 1989 Licencing Policy for Eastern Canada. In the 1996 Policy (Section 11) the provisions state that:

- S.11 (6) for fisheries restricted to vessels less than 65’ the licence will be issued in the name of an individual fisher

- S.11 (7) licence-holders restricted to using vessels less than 65’ will be required to fish their licences personally

- S.11 (8) licence-holders restricted to using vessels less than 65’ will be permitted to hold only one licence for a given species.

Following Program Review in 1995, the Policy was up-dated to reflect different priorities. Resource sustainability and economic viability continued as overarching goals, but equitable access and fleet development were dropped in favour of reducing capacity (which had grown to a multiple of what many fisheries could sustain) and preventing future growth. This change in objectives was important because it signaled a recognition by DFO that actually giving effect to sustainability and viability meant taking action to reduce demands on the resource and expectations about what the fishery could support. The Policy also set the groundwork for a different relationship with the fishing industry, one that intended to give the industry more responsibility in the decisions affecting the fisheries.

To some extent the shift in objectives made explicit in the 1996 Policy was a matter of policy catching up with reality. The Atlantic fisheries underwent profound changes after 1990, including the collapse of groundfish stocks, considerable regulation aimed at limiting capacity expansion, licence buy-backs, and a shift away from competitive fisheries to ones governed by IQs and ITQs in order to facilitate fleet rationalization as a step towards viability. But notwithstanding these shifts, some elements of policy – the owner-operator provisions in particular – remained unchanged. But as financial pressures on the inshore sector mounted and the realities of running a viable fishing enterprise became more challenging, both harvesters and processors looked for ways to circumvent what they perceived as constraints to the viability objective. The use of TAs offered one such approach.

Distribution of benefits from the fisheries

PIIFCAF, formally introduced in 2007, was one of the first policies to emerge from the Atlantic Fisheries Policy Review (AFPR) initiated by DFO in 1999. Its goal is to “… strengthen the Owner-Operator and Fleet Separation Policies to ensure that inshore harvesters remain independent, and that the benefits of fishing licences flow to the fisher and to Atlantic coastal communities.”Footnote 13 Various inshore stakeholders had indicated a need to strengthen these policies, arguing that the widespread use of trust agreements had undermined their impact by allowing many inshore licences to be controlled by interests other than the person to whom the licence had been issued.

PIIFCAF sets out what DFO describes as a “…comprehensive approach to assist harvesters to retain control of their enterprises, enhance access to capital from traditional lending institutions and maintain the wealth generated from fish harvesting in coastal communities.” At the heart of the Policy is the creation of a new licence category, Independent Core, that sets out a new eligibility criterion for a new or replacement vessel-based fishing licence: that the head of a Core enterprise (the then current licence category under the 1996 Licencing Policy) is not a party to a Controlling Agreement (CA) with respect to any inshore vessel-based fishing licences issued in their name.Footnote 14 All Core licence-holders had to sign a declaration by April 12, 2007 whether or not they met this criterion (this was subsequently extended to March 31, 2008). If they declared that they were not in a CA, then they would be categorized as Independent Core and would be eligible to be issued a licence. If no, then to be eligible for Independent Core status, the licence holder would be required to terminate the CA or amend its agreement to bring it into compliance with PIIFCAF by April 12, 2014.Footnote 15

The rationale for entering into a controlling agreement extended beyond the most commonly cited example – acquisition of the beneficial interest by a processing company to achieve vertical integration. Other reasons are operational or financial: to improve harvesting economics in IQ fisheries where transfer of quota was prohibited (groundfish in the Maritime Region); to facilitate family access an existing licence-holder acquires a second licence (because two children wish to fish upon his/her retirement) by holding the beneficial interest in the second licence through a CA in the name of a wholly-owned company until the intended child becomes eligible to hold the licence in his/her own name; to obtain financing where a prospective entrant to the fishery is unable to obtain a loan from a conventional lender (instead, enters into a financing agreement with a processing company or buyer with that agreement containing a security clause giving the plant/buyer the right to nominate a transferee; once the loan is paid off, the security would no longer be required and the licence-holder would be free to transfer the licence).

PIIFCAF covers all inshore fisheries with the exception of fleets and certain specific-purpose inshore licences that are explicitly exempted (see page 15, below). These fisheries are identified in the Commercial Fisheries Licencing Policy for each of the DFO Regions on the East Coast.Footnote 16 The inshore fisheries are ones permitted to be fished by heads of Core enterprises operating vessels less than 19.8m (65’). The broadest definition of these fisheries would be to identify each by species, though they are often further categorized by fleet (vessel size including inshore sub-categories and gear type – fixed or mobile), basis of access (quota-limited or competitive), season, and area.

Rather than try to define each according to some or other of these characteristics, the inshore fisheries are listed simply by species in Table 2 (as per the Commercial Fisheries Licencing policies). The number of licences, gear type and form of access are also provided.

Table 2: Atlantic inshore fisheries by species and DFO Region (2018)

| Atlantic inshore fisheries | Licences (#) by DFO Region | Fisheries | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maritimes | Gulf | Québec | Newfoundland | Total | Gear types | Allocation | |

| Lobster | 3,022 | 2,962 | 587 | 2,336 | 8,907 | Trap | Competitive (no TAC) |

| Groundfish | 2,373 | 1,770 | 828 | 3,261 | 8,232 | Longline/hook/trawl | IQ/ITQ/competitive |

| Mackerel | 1,985 | 3,000 | 820 | 2,137 | 7,942 | Seine/gill net | Competitive (TAC) |

| Herring | 1,803 | 2,340 | 962 | 1,991 | 7,096 | Seine/Gill net | ITQ/IQ/competitve |

| Clam | 1,154 | 2,271 | 246 | 0 | 3,671 | Dredge/fork | Competitve |

| Crab | 384 | 360 | 398 | 2,414 | 3,556 | Trap | IQ/ITQ |

| Squid | 293 | 649 | 16 | 1,955 | 2,913 | Seine/jig | Competitive (TAC) |

| Scallop | 506 | 767 | 80 | 801 | 2,154 | Dredge | ITQ/competitve |

| Capelin | 0 | 2 | 73 | 1,634 | 1,709 | Seine (purse/bar) | Competitve/IQ |

| Swordfish | 865 | 342 | 0 | 1 | 1,208 | Longline/harpoon | ITQ/Competitve |

| Tuna | 155 | 586 | 53 | 51 | 845 | Longline/rod&reel/trap | ITQ/IQ(tags) |

| Shrimp | 59 | 32 | 56 | 286 | 433 | Trawl/pot | Competitve/IQ |

| Other | 2,893 | 11,643 | 1,295 | 11,250 | 27,081 | - | - |

| Hagfish | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sculpin | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sea cucumber | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Shark | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sea urchin | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Table 2: Sources

http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fisheries-peches/ifmp-gmp/index-eng.html

http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/stats/commercial/licences-permis-eng.htm

http://www.glf.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Gulf/Licenses-Delivery/Commercial-Fisheries-Licensing-Policy

The PIIFCAF exemptions initially (2007) covered six fleets (not fisheries), distinguished by basis of access (ITQ), vessel length, gear type, and species or species group. A seventh (Tuna) subsequently qualified and was added in 2009. Theses exemptions are based in the DFO Maritimes Region (mainly in southwest Nova Scotia), where the introduction of ITQs had tended to be earlier than in the other DFO Regions on the East Coast, and where the fishery is the dominant source of economic activity in most coastal communities:Footnote 17

- Groundfish fixed gear ITQ 45-65’: this longline fleet is comprised of about 35 active vessels targeting halibut almost exclusively. It accounted for about 25% of the $40 million landed value in the halibut fishery in 2018.

- Groundfish mobile gear ITQ <65’: this trawl fleet is comprised of about 70 active vessels targeting the full range of species for which quota is available (mainly haddock in recent years). It accounted for $35 million of the total landed value in the groundfish fishery in the Maritimes region in 2018 (about $40 million, excluding halibut).

- Swordfish longline ITQ <65’: this fleet is comprised of about 120 active vessels, of which 35 or so account for 80% of total swordfish landings ($10 million in 2018).

- Herring purse seine ITQ <65’: this fleet is comprised of 11 vessels fishing 40 licences with a landed value in the $20 million range in 2018.

- Full Bay scallop: ITQ <65’: this fleet is comprised of 65 active vessels fishing 100 licences. It accounted for about 60% of total value of inshore scallop landings (about $50 million) in 2018.

- Scotian Shelf shrimp mobile gear ITQ <65’: this fleet is comprised of 9 active vessels fishing 28 licences. It produced a landed value of about $10 million in 2018.

- Tuna longline ITQ <65’: this longline fleet (comprised of most of the same vessels fishing swordfish ITQ) accounts for the bulk of tuna landings (Maritime Region total of $7 million in 2018).

Two key factors provide the rationale for these exemptions: financial and economic hardship, and the potential for disrupted fisheries. Simply stated, unwinding the arrangements would have created greater cost than the benefits obtained from imposing the policy. Requiring these exempted fleets to comply with the implementation of PIIFCAF would have caused hardship to the fleets and licence holders involved and negatively impacted the economic viability of communities in which these fleets operated.

Forcing compliance would also have resulted in significant changes to the fisheries management structure for those fisheries; the exemptions to the PIIFCAF Policy were necessary to avoid disruption to the fishery, such as an increase in the number of active vessels or individual licence holders given they could no longer “transfer” their quota or designate an individual to operate their vessel. Moreover, DFO felt it would undermine the policy to grant individual exemptions in the absence of exceptional circumstances.Footnote 18

The fleets exempted from the application of the PIIFCAF Owner-Operator and Fleet Separation policies met the following criteria:

- There was an Individual Transferable Quota (ITQ) program in place for at least 5 consecutive years;

- One of the reasons for requesting the ITQ program was to assist the fleet in self-rationalization objectives;

- The fleet experienced significant restructuring and self-rationalization as a result of the ITQ program;

- There was significant quota transfer activity under quota transfer regimes; and,

- A significant number of licences fall within paragraph 11(7) of the Commercial Fisheries Licensing Policy for Eastern Canada, 1996, that is to say, a significant number of licence holders are not required to fish their licences personally because they had previously designated an operator for one or more of their vessels and continued to do so under a grandfather clause.

Any other fleets wishing to be exempted must meet these criteria and also demonstrate:

- How an exemption would benefit the fleet;

- That an exemption for the fleet will not have significant negative impacts on other fleets;

- That an exemption will not have a negative effect on the conservation of the resource or the sustainability of fisheries; and,

- How the fleet established consensus regarding the introduction of the ITQ regime.

What qualifies as a “significant” threshold is not defined, suggesting there would be some flexibility and subjectivity (discretion) in the application of the criteria.

DFO and the inshore sector recognized that one of the weaknesses of many of the “rules” governing the Atlantic fisheries was that they were expressed in policy and not enforceable at law. Consequently, after the PIIFCAF policy had been formally introduced in 2014, DFO began in 2018 to frame its key provisions in regulation. Regulatory amendments enshrining elements of the Owner-Operator policy came into force on December 9, 2020, with regulatory amendments replacing PIIFCAF coming into force on April 1, 2021. The amendments broaden PIIFCAF by prohibiting all transfers of the use and control of the rights and privileges conferred through a licence to fish, unless specifically allowed under the regulations.

In addition to the fleets identified above, several specific-purpose licences have been exempted to avoid conflict with the regulatory amendments that would give the key PIIFCAF provisions the force of law:

- Inshore licences issued to pre-1979 companies. These processing companies held inshore licences before the fleet separation policy was introduced in 1979 and had been provided with a complete exemption from inshore policies from the outset (all the inshore policies were adopted after 1979). The licences in question (many of which are captured in the exempt fleets listed above) account for less than 1% of the total number of inshore licences, though a proportionately higher share of landed value for the fisheries in which they engage.

- When the Owner-Operator policy was adopted in the Maritimes Region, some corporations (e.g. family businesses) held inshore and coastal licences; these corporations, generally referred to as pre-1989 corporations, were grandfathered into the regime through an exception to the requirement to be an individual or wholly owned company and were allowed to continue to hold the licences.

- Inshore licences issued to Eastern Nova Scotia Snow crab companies (DFO’s Maritimes Region only). An Independent Panel created by the Minister in 2005 recommended that the temporary licences allowed to enter the fishery after the groundfish collapse be made permanent on condition they pool their individual quotas into fishing companies (an average of 10 licences per company fished by a single vessel), thereby limiting the number of additional vessels in the crab fishery.

- Inshore licences linked to allocations received by community-based fishing organizations. In each East Coast DFO Region, a number of fish harvesters’ associations, fleet planning boards or community-management boards receive allocations. Initially, these were provided in order to assist harvesters affected by sudden drastic reductions in total allowable catch (TAC) for groundfish fisheries. The allocations were then regularized such that organizations could use them as they see fit. In certain regions, a licence is issued in the regional licensing system to anchor the allocation and facilitate reporting. These organizations are not considered licence holders.

- Inshore licences issued to Indigenous organization with a commercial licence under the AFR. Indigenous organizations generally fish under licences issued under the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations and are not subject to the inshore policies (including PIIFCAF). Certain organizations (bands) also hold licences in the inshore sector that are issued under the AFRs; they were provided with a “personal” non-transferable exception from the inshore policies.

- Inshore licences issued to head of non-core enterprises. In 1996, under the newly developed Commercial fisheries licensing policy for Eastern Canada, the head of these enterprises did not qualify as “head of a core enterprise,” but was allowed to continue to hold the inshore licences issued until they retired (these licences cannot be re-issued). As of 2018, there were 3,788 such licences.

- Inshore licences issued in the name of the estate of a deceased licence holder. When a licence holder dies, the licences he or she holds can be re-issued in the name of the estate. Under the 1996 licencing policy, the estate may be given up to five years after the death to recommend an eligible person to whom a replacement licence may be issued.

- The exemptions arising from licencing constraints:

- Sculpin, only when issued with Groundfish (ITQ Mobile Gear <65’)

- Squid (jigger or handline), only when the licence-holder holds one of the exempted licences

- Squid (otter trawl), only when the licence-holder holds one of the exempted licences and an otter trawl is used to fish that licence and the licence holder does not hold other licences allowing the use of otter trawl

- Squid (purse seine), only when licence holder holds one of the exempted licences and a purse seine is used to fish that licence and the licence holder does not hold other licences allowing the use of a purse seine.

2.3 Pacific fisheries

Policy development since the 1960s

The 1976 Policy for Canada’s Commercial Fisheries applied not just to the Atlantic fisheries, but the Pacific as well. The Pacific fisheries, though differing from the Atlantic in terms of scale, structure and species, evolved in a similar manner and faced similar challenges in the years leading up to and following the extension of fisheries jurisdiction to 200 miles in 1977. On both coasts, the fisheries were characterized by rapid growth of harvesting power against a backdrop of resource fluctuations and declining abundance of key species, leading to overcapacity, short seasons and low incomes. Fleet expansion during the 1960s and 1970s could be attributed to four main factors: federal support programs for fleet modernization, open access fisheries, strong markets, and lack of strong scientific and economic underpinnings for fisheries management.

The Pacific fisheries supported many coastal communities through the first half of the 20th Century, including First Nations communities. Salmon and herring were the main fisheries, supplying numerous canneries and processing plants along the coast from Prince Rupert to Vancouver. Advances in harvesting, processing and transportation technology coupled with changing market demand contributed to a sharp rationalization of the processing sector during the 1970s and 1980s, with surviving companies and harvesters concentrated in the Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island.

The 1980s ushered in a financial crisis for the Pacific fishing industry, triggering a Royal Commission that resulted in sweeping recommendations including changes in the approach to fisheries management that would see (eventually) the introduction or expansion of output controls in the form of individual harvesting rights.Footnote 19 Footnote 20

Capacity expansion and effort control

Limited entry had been promised as early as the 1950s as a first step in grappling with the problems created by overcapacity, but it was not until 1969 that the policy was implemented, initially in the salmon fisheries and extending to other key fisheries – roe herring (1974), spawn-on-kelp (1975), trawl (1977), abalone and shrimp by trawl (1977), halibut (1979), and sablefish (1981), geoduck (1983) and shrimp by trap (1990).Footnote 21

Limited entry, by itself, did little to slow the expansion of harvesting capacity since the incentive to maximize shares in what were then competitive fisheries remained. In the ensuing years, limited entry was complemented with a range of other input controls aimed at constraining and reducing capacity: vessel replacement restrictions, gear restrictions, open times, trip limits, and even buying back licences. Their effectiveness was limited, due mainly to weak replacement rules and allowing licence transfers.Footnote 22 Even today, excess capacity in several key fisheries (salmon, herring, groundfish) is seen as a major impediment to achieving economic objectives (income, viability).Footnote 23

Owner-operator

With most of the vessels deployed in the Pacific fisheries measuring less than 40’, the fleet resembled the inshore sector on the Atlantic coast. But the resemblance stopped there. An important difference was that from the late 1960s licences in most key fisheries were issued to vessels (salmon, groundfish, crab, shrimp, and geoduck), rather than to individual harvesters as in the Atlantic fisheries.Footnote 24 Moreover, with a few exceptions, Pacific licencing was not subject to an Owner-Operator policy. Companies, including fish processors, could own and operate vessels (and associated licences) using hired skippers and crews.

The roe herring fishery was an exception (initially) to the policy of licencing vessels. With the introduction of limited entry in that fishery in 1974, non-transferable licences were issued to individuals with an owner-operator provision (this applied to new entrants only, not existing licence-holders).Footnote 25 The fishery was greatly overcapitalized; non-transferability was an attempt to reduce vessel numbers through attrition (and also to prevent acquisition by processing companies). The owner-operator provision was removed in 1979 because DFO found it difficult to enforce. Non-transferability, circumvented through various mechanisms including leasing and trust agreements, proved difficult for DFO to enforce. The restriction was removed in 1990, allowing licence-holders to recommend to whom replacement licences would be issued.Footnote 26

The concern over corporate ownership and/or control of licences was at the forefront of a Commission of Inquiry into DFO licencing policy conducted in 1991. This Commission was appointed, not by government, but by certain fishing industry organizations representing fishermen, vessel owners and licence holders in the British Columbia fishing industry who were dissatisfied with then current licencing policy. Its terms of reference instructed the Commissioner to investigate and develop alternatives to the licencing policy provisions contained in DFO’s 1990 discussion paper, Pacific Region Strategic Outlook. Vision 2000: A Vision of Pacific Fisheries at the Beginning of the 21st Century. Among the Vision’s stated objectives:

- Optimal sustained exploitation rates

- Consultation with the fishing industry and the public

- Equitable allocation arrangements which allow participants an optimum share in the benefits

- Improved stability for the commercial fishing industry

- Expansion of the economic and social viability of coastal communities

The Inquiry report argued that corporate control of licences was inconsistent with licencing policy since the licence is the privilege granted to those actually harvesting the public resource. The companies to which licences were issued were not the ones doing the harvesting. The report applied the same reasoning to licence-holders who did not actually fish but leased their fishing privilege to others. The report argued that in both instances, the Minister’s right to determine who harvests the resource was “usurped” by other individuals.Footnote 27 The Commission of Inquiry recommended that all licences issued by DFO include a provision that they will be owner-operated (this recommendation was accompanied by several supporting recommendations). These recommendations would appear to have lacked broad harvesting sector support of the kind that led initially to the implementation of PIIFCAF in the Atlantic fisheries, and then to regulatory amendments covering fleet separation and owner-operator.

Fleet separation

Processing companies were not restricted from owning vessels and the associated licences, though a cap of 12% of total licences in the salmon fishery was announced in 1970 under Phase 2 of the Davis Plan. This cap was implemented not through regulation but a form of “gentlemen’s agreement” policed informally by DFO. As one commentator queried, “Without Atlantic style safeguards, did the feared corporate takeover occur in British Columbia? The situation at the end of the millennium [1999] was murky.”Footnote 28 In its 1991 report, the Commission of Inquiry stated that:

“Large processing companies and other fleet owners are thought, for example, to control an inordinate share of the salmon seine and roe herring seine licences. The current opinion among fishermen is that more than 80 per cent of these licences are unavailable to independent fishermen. The magnitude or seriousness of this problem is difficult to determine since Fisheries and Oceans does not require this kind of information about the licences as part of the licence application process.” (at p. 20)

It is difficult to find references in published documents to any policy or management decisions that affirm an explicit movement away from the 12% cap. Even the existence of the cap seems to be in question, notwithstanding the Minister’s 1970 announcement in footnote 26. For example, in a 2018 commentary on amendments to the Fisheries Act, the BC Seafood Alliance stated, “Licences in virtually all fisheries in BC since then [1969] have been fully transferable and available to processors.”Footnote 29

Distribution of benefits from the fisheries

The Pacific Region currently lacks general measures corresponding to the Atlantic’s Fleet Separation and Owner-Operator policies aimed at supporting a fair distribution of benefits from the fisheries (these policies operate vertically between the harvesting and processing sectors, and horizontally across licences within specific fisheries). Though the Vision 2000 policy objectives expressed support for “optimum share in the benefits” and “economic and social viability of coastal communities”, it is difficult to find general regulatory or policy measures aimed at achieving them. Such measures do operate at the fleet level, for example, the Groundfish Trawl fishery Groundfish Development Quota and Code of Conduct Quota introduced in 1997 provide that 20% of the groundfish trawl and hake TACs be set aside for allocation by the Minister, subject to advice given to him/her by the Groundfish Development Authority (GDA) that considers fair crew treatment, regional development, stable markets, employment conditions, and sustainable fishing practices.

Most fisheries also have limits on consolidation that could provide a basis for horizontal distribution of benefits across licence-holders in specific fisheries. These take different forms depending on the fishery: limits on stacking of licences, stacking of trap allocations, and quota holdings. But the distributional objectives are blunted because these limits apply only at the licence level. Without limits on the number of licences an entity can hold, concentration of benefits is possible.

Though it does not intend to do so, the regulatory framework (tradable quotas) aimed at promoting fleet rationalization in fisheries with excess harvesting capacity also facilitates the drain of revenue from active fishers resulting in the concentration of benefits in a rentier class of quota investors. This would appear to be at odds with how the benefits of the privilege embodied in the fishing licence were originally intended to flow;Footnote 30 it is also at odds with current Pacific fisheries objectives including promoting the stability and economic viability of fishing operations and encouraging the equitable distribution of benefits (listed on page 22, below).

3. Applying Atlantic fisheries policies in the Pacific Region

3.1 Atlantic policies designed to support independent harvesters

In addition to PIIFCAF, several other measures designed to support independent harvesters in the Atlantic fisheries are of note:

- Policy to regulation: The Atlantic Fishery Regulations, 1985 and the Maritime Provinces Fishery Regulations have been amended to incorporate key elements of the inshore policies. The amendments published on December 9, 2020 prohibit licence holders from transferring the rights and privileges conferred under the licence; restrict the issuance of inshore licences to licence holders who have not transferred the rights and privileges conferred under the licence; and prohibit any third party from using and controlling the rights and privileges associated with a licence.

- Substitute operator policy: On application, an operator (Independent Core or Core licence- holder) may designate a substitute operator to fish the applicable licences. The policy sets out the criteria the operator must meet to qualify and the maximum duration of a substitution (up to five years in the case of a substitution for medical reasons). This policy provides the operator with flexibility to continue in the fishery if circumstances permit, or to sell the enterprise.

- Notice and acknowledgement policy: The Notice and Acknowledgement (N&A) System is used to notify DFO of an agreement between a licence holder (LH) and a Recognized Financial Institution (RFI) and/or a Community Development Board or Organization. Once DFO is notified of an agreement between an RFI and a LH through the N&A application, a note is added to the LH’s file. If he/she recommends the reissuance of the licence, the RFI is notified and DFO will wait until their acknowledgement before proceeding with the "transfer". This allows additional security to the RFI that the licence will not change hands without their knowledge. This is intended to address one of the reasons why harvesters enter a CA: to secure financing from a processor, buyer or other licence-holder to purchase a vessel or licence. By excluding this kind of arrangement from the definition of a CA, it allows the RFI to use the licence as security for the loan.Footnote 31

- Issuing licences to companies: During PIIFCAF consultations DFO heard considerable support for allowing vessel-based licences to be issued to companies wholly-owned by an Independent Core licence holder. A new Policy on the Issuance of Licences to companies came into effect in 2011. This allows Independent Core licence holders to incorporate a wholly-owned company that will be issued the licence, creating several benefits: Limited liability of the unique shareholder of a corporation, taxation at the lower small business rate, potential to claim enhanced capital gains exemption upon the sale of the shares, and greater flexibility in estate and succession planning.

- Combining and licence stacking: CAs had been used to circumvent the Owner-Operator policy that effectively limited a harvester to holding only one licence per species/gear type. Licence- holders are permitted to combine two licences (e.g., lobster, snow crab, with 150% of the permitted gear) and fish them from a single vessel, thereby gaining operating efficiency. Also, in certain community-based IQ groundfish fisheries, harvesters may combine licences to achieve self-funded fleet rationalization and operating viability.

3.2 Pacific fisheries stakeholder perspectives on implementing Atlantic policies

Overview

We reached out to a few stakeholders to gain some insight into the range of views on the issues examined in this report. This was not intended to be, and nor should it be seen as, a comprehensive consultation. Stakeholders contacted provided important perspectives on the evolution of Pacific fisheries and the relative merits of implementing Atlantic policies to achieve Pacific policy objectives.

These policy objectives were outlined in testimony to the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans in 2019:Footnote 32

- Conservation outcomes;

- Compliance with legal obligations, such as First Nations rights;

- Promoting the stability and economic viability of fishing operations;

- Encouraging the equitable distribution of benefits; and

- Facilitating the necessary data collection for administration, enforcement and planning purposes.

The views of two organizations representing a broad cross section of Pacific fishing industry interests are summarized below. These perspectives are based on interviews and information drawn from published sources.

British Columbia Seafood Alliance (BCSA)

The BCSA opposes the introduction of Atlantic fisheries policies – specifically Fleet Separation and Owner-Operator – in the Pacific fisheries. In its 2018 presentation on quota licencing policy to the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans during its consideration of Bill C-68 (An Act to amend the Fisheries Act), the BCSA summarized its position as follows:Footnote 33

- “The Atlantic/Quebec owner operator provisions as outlined in the consultation document have no relevance to BC. DFO should therefore reject all comments (including ours) that relate to the West Coast unless and until it is ready to initiate a full-scale policy review for Pacific Canada.”

- “Such a review must require a firm footing of empirical evidence rather than assertions made by any party with little or no evidence to back them up. This cannot be done quickly and cannot be done without industry engagement.”

- “A review is necessary because the proposed Atlantic/Quebec amendments simply enshrine existing policy, developed from 1979-1989, in regulation. There are few significant changes, simply some clarification of existing rules and procedures. This would not be the case for Pacific Canada, where no such policies exist. Instituting a similar policy on the West Coast would overturn even more decades of legal practice to meet conservation and economic viability requirements.”

In support of its position, the BCSA goes on to note that fisheries management in Canada has evolved differently on its east and west coasts. Several factors that would explain these differences are offered. Though the fisheries did evolve differently, the points of distinction as stated by the BCSA are perhaps less sharp than indicated. The author’s observations are not meant to dispute the validity of matters pertaining to the Pacific fisheries, but rather simply to clarify points as they apply to the Atlantic fisheries.

- “Atlantic policy has been driven by adjacency (protecting provincial fishery access) and maintaining an inshore/midshore fleet of <65’ to protect often remote rural coastal communities. With only one coastal province, the adjacency principle does not apply.” Maintaining a strong inshore fleet to preserve the economic viability of coastal communities was certainly a driver of policy, and integral to that was the adjacency principle. But the adjacency principle is not limited to provincial or regional boundaries; it operates at the sub-provincial level through licencing policy by restricting the transfer of licences to residents of the same fishing area to which the licence applies (e.g., in the Atlantic fisheries there are 40 Lobster Fishing Areas; 24 snow crab fishing areas; etc).Footnote 34

- “For more than a century, processors have provided boats and gear or provided short term loans to enable fishermen to go fishing.” The same approach, with many variations including providing administrative services, has been used on the east coast for over 200 years. The motivation was not altruism, but to secure the boat’s catch.

- “Limited entry licencing in 1969 for salmon and later for virtually all fisheries, the first of many attempts to reduce too many boats chasing too few fish, inevitably created value in licences. In virtually every case, limited entry licencing resulted in too many licences for a fishery.” Limited entry began with lobster in 1967 and was introduced gradually in other fisheries during the 1970s. This created value in licences in the Atlantic fisheries. And in almost all fisheries, the number and capacity of boats permitted to enter exceeded sustainable harvest levels. More stringent input controls including vessel replacement restrictions, gear limits, catch limits, etc., had limited effect. With competitive fishing providing an incentive to maximize the share of the catch, the pressure to over-capitalize continued.

- “This excess capacity was incompatible with both conservation objectives (weak stock management, precautionary harvest levels, increased accounting of directed and non-directed catch) and economic viability. Many fisheries therefore started adopting new management measures (Individual Vessel Quotas, area licencing, licence stacking) as a means to rationalize excess capacity and provide economic benefits to remaining operators.” The introduction of IQs and ITQs occurred at the same time (from 1990 on) and for the same reasons in the Atlantic inshore fisheries. The use of individual quotas (or enterprise allocations as they were termed) actually dates from 1976 in the herring fishery and 1982 in the offshore groundfish fishery. Licence stacking was prohibited, though effectively practiced through the use of short-term (seasonal) quota leasing, owner-operator rules notwithstanding. Combining/stacking licences in some fisheries (e.g., lobster, crab) to improve efficiency also began to be permitted by DFO.

- “Licences in virtually all fisheries in BC since then [1969] have been fully transferable and available to processors.” This seems to be at odds with published sources where a limit on corporate ownership in the salmon fishery was announced by the Minister in 1970.Footnote 26

- “Most, but not all, limited entry licences are vessel-based rather than party based as in Atlantic Canada. Multiple ownership of a vessel is common and means multiple ownership of the associated licences and quota.” As noted, licencing is the main point of departure between the Atlantic and Pacific fisheries. Issuing the licence to the individual when combined with the owner- operator rule respects the spirit and letter of the law that the fishing privilege/right is conducted by the licence-holder. Under PIIFCAF, there are exemptions (See above). For example, as a means of limiting the number of vessels in the Eastern Nova Scotia snow crab fishery, licences were issued to several companies comprised of up to 10 vessel owners who agreed to combine the individual quota associated with their licences into a single company quota fished by one of the shareholder- owned vessels.

- “For the groundfish fisheries, this culminated in the Commercial Groundfish Integrated Program (CGIP) which integrates the management of some 66 different stocks, seven fisheries and three gear types (trawl, trap and hook and line). Roughly 2/3 of the volume of BC landings operates under CGIP. CGIP requires full accountability for every fish caught, whether retained or discarded, to allow for accurate assessment of all mortalities. It also requires 100% at sea-monitoring and 100% dockside monitoring. It is a world class program, but it could not operate without temporary transfers (leasing) quota to cover bycatch, often of vulnerable or Endangered, Threatened and Protected species.” Temporary transfers to cover by-catch and to facilitate fishing plans is a feature also of the relevant inshore groundfish fisheries in the Atlantic. Though not as complicated as the Pacific groundfish fishery, the principle and practice are the same.

Canadian Independent Fish Harvesters’ Federation (CIFHF)

The CIFHF and its BC members support the introduction of owner-operator and fleet separation policies in the Pacific fisheries. In a discussion with the author, CIFHF representatives provided the following arguments in support of their position.Footnote 35 These points cover much the same ground as many of the presentations made by the BC harvesters who appeared as witnesses before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries during its public hearings in January and February 2019. Observations by the author on these points appear in italics.

- In general, the owner-operator and fleet separation policies represent the only hope for improving the economic viability of the harvesting sector. By redressing the balance between risk and benefits in the fisheries, these policies would restore and strengthen the economic foundation of coastal communities, particularly in northern BC. These policies may be a necessary condition for achieving the stated outcomes but not necessarily sufficient. Also required are a management regime that supports the recovery of salmon stocks and other species and allows fleets to achieve an economic balance between harvesting capacity (costs) and allowable catch (revenue).

- Redressing the balance between risk and benefits in the fisheries is key to enterprise viability and securing the results that flow from it, namely, generating: sufficient personal income (after costs have been covered) to retain experienced skippers and crews; sufficient revenue to cover operating costs; a sufficient return on investment to attract capital to replace vessels and gear; and sufficient income and favourable working conditions to attract new entrants to the industry. The best examples of the kind of balance between risks and benefits needed to support enterprise viability may be found in the same fisheries often cited as examples where risks and benefits are not in balance. These occur in circumstances where the vessel fishes the quota on its own licence, rather than leasing quota from others at high prices relative to the shore price for the catch.

- Within this set of results, attracting new entrants presents a major challenge. This is because returns on investment are typically too low to service the debt to secure a licence.Footnote 36 Licence prices are high and represent a major barrier to entry; but licence prices are high because few are on the market due to the attractive income stream they generate for inactive licence (quota) holders through leasing. In key fisheries, substantial shares of quota are held as investments either by the licence-holder who originally was granted the quota, or by investors outside or inside the industry who can afford to buy them (and the associated licence). While there seems to be agreement that leasing and the impact it has on access and enterprise viability is a major impediment to attracting entrants to the fisheries, the evidence to support this tends to focus narrowly on the halibut fishery where the implications of leasing on harvester economics has been documented.Footnote 37 Presumably, the argument would be strengthened if the experience in other fisheries could also be documented (e.g., sablefish, groundfish). Attracting entrants has been and continues to be a challenge also in the Atlantic fisheries, not because of leasing, but due to high licence prices in the major fisheries (e.g., lobster and crab). This is a function of scarcity (demand vs. supply of licences) and the expected profitability of the fishery in question.

- While there may be some disagreement on the proportion of quota that is passively leased by inactive quota-holders and investors, there seems to be no disagreement within the industry on the impact this practice has on active harvesters, specifically, creating an imbalance in how risks and benefits are shared.Footnote 38 For many, access to the fishery is through the quota they are able to lease. Leasing arrangements are structured so that the harvester bears substantial financial risk as well as the usual operating risks. High leasing costs in several fisheries leave vessels with revenue to cover operating costs, while the revenue needed to cover current and future capital requirements accrues as profit to the rentier quota-holder or licence-holder.Footnote 39 Footnote 40 As the licence is understood by most in the industryFootnote 28, the licensee (harvester) is to gain access to the privilege of fishing a public resource directly from the licencing agency (DFO), not through the uncertain and costly agency of a third-party.

- Adoption of a strictly enforced owner-operator policy in the Pacific fisheries would preclude this practice (indefinite leasing), resulting in the retention of fishery revenues to support much needed investment in fleets and infrastructure, as well as improved incomes for harvesters. This would further Pacific fisheries policy, namely, promoting the stability and economic viability of fishing operations, and encouraging the equitable distribution of benefits. In-season quota transfers and leasing amongst active vessels would continue, allowing harvesters to optimize their fishing plans. This would be consistent with the owner-operator approach in Atlantic fisheries where in-season leasing is permitted.Footnote 41

- The CIFHF and its BC members also recognize that a transition to an owner-operator fishery could not occur overnight. As one fisher envisaged the process:Footnote 42

- “Looking at the long term, we need to find common ground and look at where we need to be 10 years from now as an industry, and then design and implement well-thought-out specific policies that will get us there. I see a sustainable fishing industry in B.C.'s future being made up of fishermen and fish processors. The timelines for the industry's future must allow sufficient time for investors and retiring fishermen to divest and retire with dignity.”

3.3 Lessons learned from implementing PIIFCAF policies

Industry perspective

Leaders of several of the CIFHF member organizations provided insight into why the process culminating in PIIFCAF had become necessary, and offered guidance on how to maintain the integrity of the owner-operator and fleet separation policies:

- PIIFCAF had become essential because DFO had over the years allowed the erosion of the key policies – owner-operator and fleet separation – by permitting various exceptions and by turning a blind eye to actions taken by industry to sidestep the rules, for example, through the use of trust agreements. A concerted effort by leading harvester organizations was needed to persuade DFO to take action. The prevailing view amongst these organizations is that it is DFO’s responsibility to ensure its own management principles and policies are respected and enforced.

- The fishery as a source of direct and indirect employment and income is vital to community economic stability. Owner-operator and fleet separation are key policies for maintaining a viable fishery, and hence key to community stability.

- DFO allows officials in its Regions too much autonomy in determining how they will apply basic policy and implement management measures. Such differences exist not just between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, but among Regions in Atlantic Canada. Some Regional differences are understandable given differences in how fisheries have evolved; but overarching policy measures should be applied and enforced uniformly.

- DFO had no will to enforce the process to root out controlling agreements when the approach was announced in 2007. Harvester organizations had to keep the department’s feet to the fire in order to ensure declarations were forthcoming. In any future process of this kind, declarations should be required annually from the outset in clearly worded statements with adequate penalties for non-compliance.

- DFO should have minimized exemptions since they make it clear that those who would break the rules would be rewarded for their actions. Exemptions set a bad precedent. The same rules should apply to all.

- Securing exemptions seemed to have rewarded the lobbying efforts of the fleets in question. The criteria would appear to have followed the decisions, and not established in advance.

- Seven years was longer than needed to rectify controlling agreements. This gave industry too much time to develop new workarounds to PIIFCAF. Three to four years should have been enough.

DFO perspective

DFO officials have identified three main lessons emerging from the process of implementing PIIFCAF policies (in fairness, these are more in the nature of lessons confirmed than learned):