Information about Pacific salmon

Please see our glossary of salmon terms for more information.

Chinook salmon

Chinook salmon

Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

Quick Facts:

- Scientific name: Oncorhynchus tshawytscha.

- The chinook is the largest of the Pacific salmon species, the world record standing at 57.27 kilograms (126 pounds).

- Chinook are also known as "spring" salmon because they return to some rivers earlier than other Pacific salmon species.

- This species is known as piscivorous, meaning that they eat other fish.

A favourite in the recreational fishery, the chinook salmon is known by many names: King, blackmouth, quinnat, and chub are all references to this powerful fish - with those over 14 kilograms (30 pounds) dubbed "Tyee".

Chinook, which spawn in large rivers from California to Alaska are found in a relatively small number of streams in BC and the Yukon. Chinook production happens mainly in major river systems, the most important of which in BC is the Fraser River. Substantial numbers of chinook are also found in the Yukon River.

After hatching, chinook remain in fresh water for varying lengths of time depending on water temperature. In southern areas, some migrate after three months in fresh water while others may remain for up to a year. In northern areas, most chinook spend at least a year in fresh water. These fish are known to migrate vast distances and are found sparsely distributed throughout the Pacific Ocean. The age of chinook adults returning to spawn varies from two to seven years. Many river systems have more than one stock of chinook, some even having spring, fall and winter runs.

Because of their large size and presence in coastal waters, chinook are one of the favoured prey of killer whales, and recreational and commercial fishers. Chinook are typically fished in "hook and line" fisheries where they chase and bite lures or baited hooks being trolled through the water. Chinook are an unusual Pacific salmon species because the flesh of adults can range in colour from white through pink to deep red.

While still feeding in tidal waters, the chinook has a dark back, with a greenish blue sheen. As they approach fresh water to spawn, the body colour darkens and a reddish hue around the fins and belly develops. The teeth of adult spawning males become enlarged and the snout develops into a hook.

For further identifying information about chinook salmon, please see our Recreational Fishing Salmon Identification pages.

Chinook Migration Map

Chum salmon

Chum salmon

Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta)

Quick Facts:

- Scientific name: Oncorhynchus keta.

- Chum salmon are found throughout the Pacific Rim, from Oregon to Alaska and as far afield as Japan and Korea.

- Chum are the poorest jumpers of the Pacific salmon world and waterfalls that do not impede any of the other species can often stop their upstream migration.

- This is a preferred fish for cold-smoking, owing to the low oil content of the flesh.

Commonly referred to as dog salmon due to the appearance of mature males, chum is the least sought-after of the Pacific salmon species, though has long provided a food staple for coastal peoples due to its abundance in the region.

In BC and the Yukon, chum spawn in more than 880 medium-sized streams and rivers. In short coastal streams, chum emerge from gravel spawning beds in the spring as fry and move directly to the sea. This migration is accomplished in a day or two. In larger river systems, the young remain in fresh water for periods of up to several months before reaching the ocean. Most chum spend two or three summers at sea before returning to their home streams to spawn. In May or June of their final year at sea, maturing chum are found throughout the eastern and western Pacific, north of the California border.

An attractive fish, in tidal waters chum are metallic blue and silver, with occasional black speckling on the back. Spawning chum are readily recognized by the dark horizontal stripe running down their sides, the canine-like teeth of the large males and the checkerboard or calico colouration. Chum salmon are the most widely distributed of the Pacific salmon.

For further identifying information about chum salmon, please see our Recreational Fishing Salmon Identification pages.

Chum migration map

Coho salmon

Coho salmon

Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch)

Quick Facts:

- Scientific name: Oncorhynchus kisutch.

- There are more distinct populations of coho than of any other Pacific salmon species in BC.

- Although coho tend to remain close to the coastline, they have been found as far as 1600 km from shore.

- Juvenile coho defend their territories through a series of maneuvers including a complex shimmy-shake, dubbed by scientists the "wig-wag dance".

Coho are swift, active fish. These salmon are found in most BC coastal streams and in many streams from California to Alaska, but their major territory lies between the Columbia River and the Cook Inlet in Alaska. Coho spawn in over half of the 1500 streams in BC and Yukon for which records are available.

Young coho generally spend one year in freshwater although in northern populations, high proportions of juveniles spend two or even three years in freshwater before entering the ocean. Juvenile coho favour small streams, sloughs and ponds, but coho populations can also be found in lakes and large rivers. After the eggs hatch in the gravel of stream beds, young coho spend one-two years rearing in freshwater. Migrating as smolts to the oceans, they spend up to 18 months in the sea before returning to their natal streams to spawn. While most coho salmon return to fresh water as mature adults at three years of age, some mature earlier and migrate to their home streams as jacks at only two years.

There is only so much space for territories in streams so the number of young coho is limited and there is intense competition for what space there is. Individuals that can not find or defend a territory do not survive well. A consequence of this territoriality is that a stream tends to produce the same number of smolts year after year regardless of the number of adults that spawn in it.

Unlike other salmon species which generally migrate long distances in the open ocean, coho remain in coastal waters. Their proximity to land, their willingness to take lures and their tendency to jump and dodge makes them a favourite among sport fishers. Coho are also caught in First Nations food fisheries by traditional methods of weirs, nets and gaffs. Commercial troll fisheries have long harvested coho as well, although recent population instability has prompted ongoing restrictions in all fisheries since 1998.

As adults, coho have silvery sides and a metallic blue back with irregular black spots. Spawning males in freshwater exhibit bright red on their sides and bright green on the back and head, with darker colouration on the belly. They also develop a marked hooked jaw with sharp teeth. Female spawners also change colour and develop the hallmark hooked snout, but the alteration is less spectacular.

For further identifying information about coho salmon, please see our Recreational Fishing Salmon Identification pages.

Coho migration map

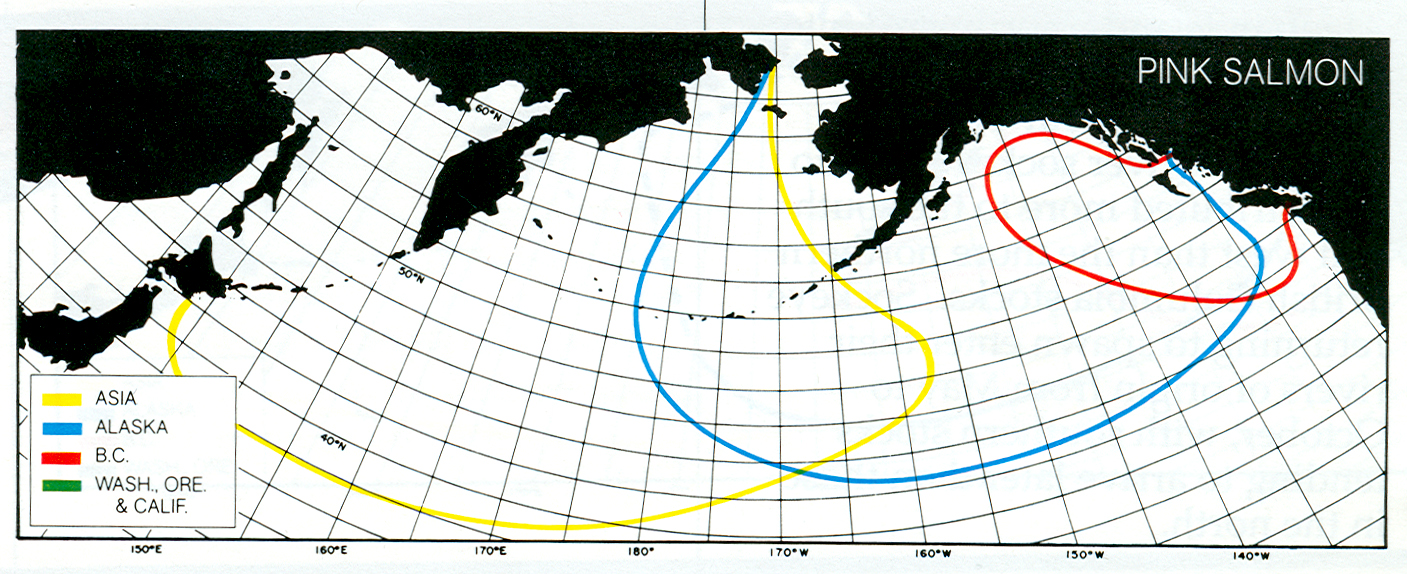

Pink salmon

Pink salmon

Pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha)

Quick Facts:

- Scientific name: Oncorhynchus gorbuscha.

- Pink salmon are the most abundant of the seven species of salmon in BC waters.

- Pinks have a short, two-year lifespan.

- Fishermen know these salmon as "humpbacks" or "humpies" due to the humped back developed in males as they return to spawn.

This species is found in streams and rivers from California north to the Mackenzie River, with their principal spawning areas between Puget Sound, Washington, and Bristol Bay, Alaska. They migrate to their home stream from July to October, and while some go a considerable distance upstream, the majority spawn in waters close to the sea. During the spawning period, both sexes change from their blue and silver colouring to a pale grey.

A peculiarity of this species is its fixed, two year lifespan. Immediately after they emerge from the gravel in the spring, the young pink fry enter the ocean and after a few days to several months in the estuary and nearshore zone, they move out into the open ocean in large schools. There, pink salmon feed on the small and nearly invisible animals called zooplankton, especially krill, which gives their flesh the bright pink colour for which they are named.

Despite their short life span and small size, the migrations of Pink salmon are extensive, covering thousands of kilometres from their home streams. During ocean feeding and maturing, pink salmon are dispersed throughout the Pacific Ocean from northern California to the Bering Sea. During fall and winter, pink salmon spend more time in the southern parts of their range.

Pink salmon are mainly caught by purse seine, gillnets or trolling gear. Troll catches are normally sold as fresh fish, while those taken by net are most often canned. Recreational fishers generally catch pinks with the use of artificial lures.

For further identifying information about pink salmon, please see our Recreational Fishing Salmon Identification pages.

Pink salmon migration map

Sockeye salmon

Sockeye salmon

Sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka)

Quick Facts:

- Scientific name: Oncorhynchus nerka.

- Sockeye were the first salmon to be harvested commercially in the Pacific Region

- The rich colour and oil content of sockeye may be attributed to their diet which includes a high percentage of shrimp and other crustaceans.

- The name sockeye is believed derived from the Coast Salish name "sukkai" at one time in common usage in southwest BC.

The best known Pacific salmon, sockeye are the most sought after for their superior flesh, colour and quality. Their rich oil content and red colour make them a favourite with the Canadian and international public.

The main spawning area of sockeye salmon extends from the Fraser River to Alaska's Bristol Bay. Most sockeye in BC and the Yukon spawn in late summer or fall in lake-fed systems; at lake outlets, in lakes, or in streams flowing into lakes. Major spawning runs are found in the Fraser, Skeena, Nass, Stikine, Taku and Alsek watersheds as well as those of the Smith and Rivers inlets.

Young sockeye may remain in their freshwater nursery lakes for a year or more, with some waiting until the second or third year to make their seaward journey. Once in salt water, BC sockeye move north and north-westward along the coast. Their maturing years find them in a huge area of the Pacific Ocean extending west to approximately the International Date Line (2600 miles from the coast of Vancouver Island), north to the northern Gulf of Alaska and south to the Oregon-California border.

One of the most remarkable features of sockeye is a phenomenon called "cyclic dominance". In many of the lakes of the Fraser River in particular, sockeye are abundant in one of every four years. Sockeye can mature at ages between two and six years old but in most systems, one age group (usually four-year-old fish) dominates, meaning most of the offspring produced in any one "brood-year" return to spawn four years later. This year of increased population significance creates a cyclic dominance which leads to spectacular returns to the Adams River every four years. Although there are many ideas about why this occurs, nobody knows for sure.

Sockeye salmon are caught commercially with purse seine, gill nets and trolling gear. First Nations use traditional nets, weirs and gaffs; while sport fishers are able to catch sockeye with spoons or bait. Migratory pathways present the greatest availability for catch during runs from June to November. Significant to all fishing sectors, sockeye were the first salmon to be commercially fished in the Pacific Region and were the first salmon to be canned in quantity, beginning in the 1870s.

Although ocean-going sockeye are silver in colour, with small black speckles along the body, the recollection many people have of this fish is that of the sockeye returning to freshwater to spawn. As sockeye approach their home streams, they turn varying shades of red - resulting in a brilliant scarlet fish with a green head by the time they have arrived at their point of natal origin. It is this deep colouring, along with the rich cultural, economic and ecological history that continue to make sockeye a symbol in the Pacific Region.

For further identifying information about sockeye salmon, please see our Recreational Fishing Salmon Identification pages.

Sockeye migration map

Lifecycle of a salmon

Lifecycle of a salmon

Lifecycle of a salmon

Each fall, drawn by natural forces, the salmon return to the rivers which gave them birth. They fight their way upstream against powerful currents, leap waterfalls and battle their way through rapids. They also face dangers from those who like the taste of salmon: bears, eagles, osprey and people.

Once the salmon reach their spawning grounds, they deposit thousands of fertilized eggs in the gravel. Each female digs a nest with a male in attendance beside her.

By using her tail, the female creates a depression in which she releases her eggs. At the same time, the male releases a cloud of milt. When the female starts to prepare her second nest, she covers the first nest with gravel which protects the eggs from predators. This process is repeated several times until the female has spawned all her eggs.

Their long journey over, the adult salmon die. Their carcasses provide nourishment and winter food for bears, otters, raccoons, mink and provide nutrients to the river for the new generation of salmon, much as dying leaves fertilize the earth. The two other salmonids, cutthroat and steelhead, may survive to go back to sea and possibly return to spawn again.

As the salmon eggs lie in the gravel they develop an eye - the first sign of life within. Over months, the embryo develops and hatches as an alevin. The alevin carries a yolk sac which will provide food for two to three months. Once the nutrients in the sac are absorbed, the free-swimming fry must move up into the water and face a dangerous world.

The fry may live in fresh water for a year or more, or may go downstream to the sea at once - it varies by species. Fry ready to enter salt water are called smolts. Whenever they do migrate, they face predators, swift currents, waterfalls, pollution and competition for food.

Young salmonids stay close to the coastline when they first reach the sea. After their first winter, they move out into the open ocean, and, depending on the species, spend from one to four years eating and growing in the north Pacific Ocean. Then they return to their home streams, spawn and die.

From each thousand eggs that were laid, only a few adult salmon survive to perpetuate their species. Hatcheries greatly increase the number of survivors by protecting the eggs and fry through the critical early development of their life.

- Date modified: